Don't Pack the Courts, Improve Them

In early March, when it appeared that Senator Bernie Sanders had clinched the nomination in the Democratic primary, I wrote that Democrats should come together to support his candidacy but also push back against his more radical and less democratic impulses while he was in office. I was later surprised and impressed by the unity of the moderate wing of the Democratic Party in pushing back against the party’s less democratic impulses, something that is rarely seen in opposition parties facing a polarizing incumbent like President Donald Trump.

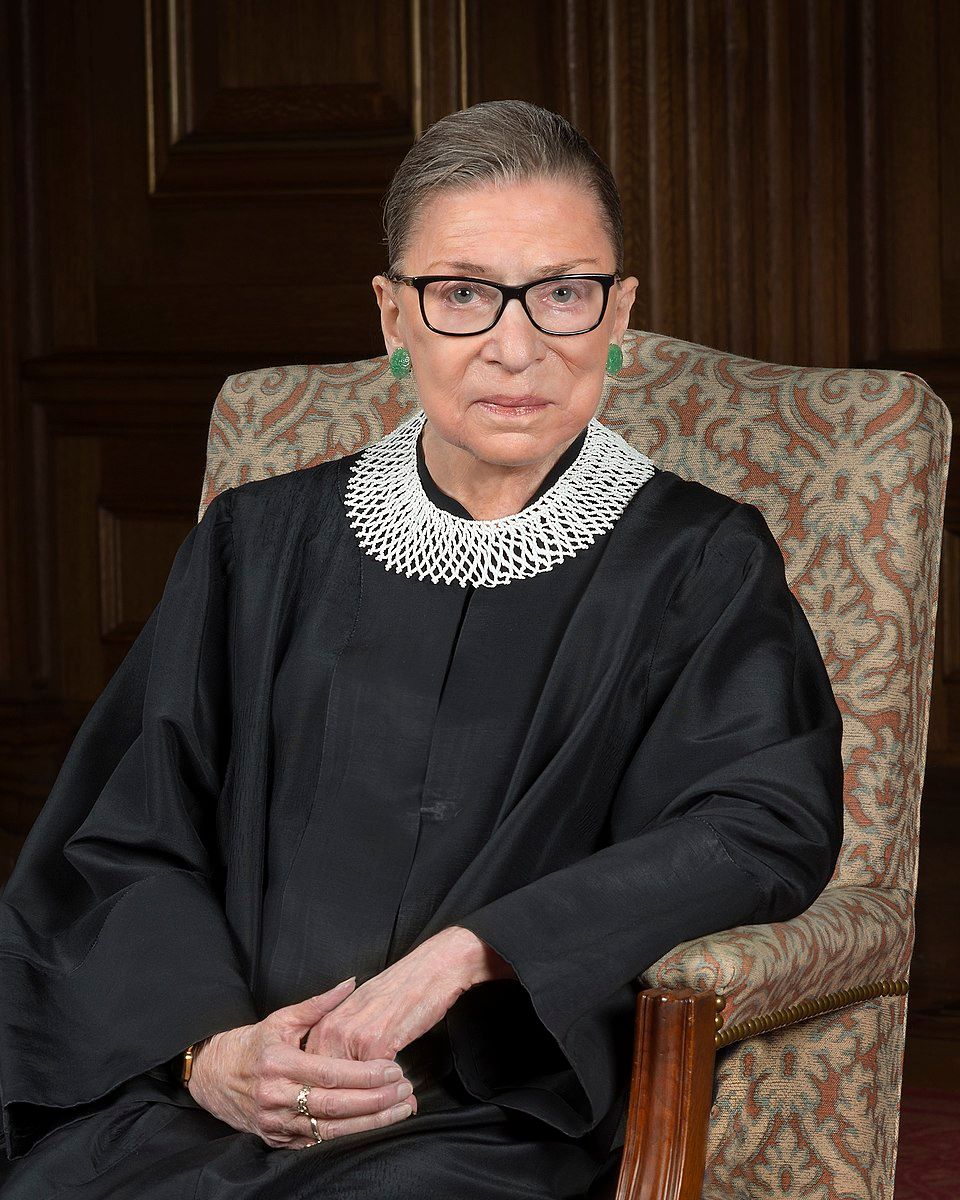

Following the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, conflict, not only between Democrats and Republicans but between the left wing and the moderate wing of the Democratic Party, came to the fore once again. Leftists shared searing criticisms of the late justice and moderates mourned the loss of a beloved icon. However, following a viral tweet by New York Times opinion columnist Jamelle Bouie, one area is emerging as a surprising point of convergence: court packing.

Court packing, as it has been generally proposed and understood, would involve adding two justices to the court to balance against the seats, that are perceived to have been wrongfully stolen from the Democrats — Scalia’s in 2016, when Republicans prolonged the confirmation process until after Trump’s election, and now Ginsburg’s. Most popular proposals for this kind of court packing would bring the total number of justices up to 11. In the past, court packing was most notably supported by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who wanted to add a new justice to the court for each justice who refused to retire after 70, bringing the court to as many as 15 judges. In modern American politics, court packing has generally been embraced by the left and progressive wing of the party while avoided by moderates for fears of setting a dangerous precedent — the manipulation of the court’s size by each incoming party to remove a check on its legislation.

For many, that calculus seems to have changed. Journalists and academics ranging from the far left to the center-right have noted that Trump’s appointees share “a dubious distinction.” They are the only justices in American history appointed by a president who lost the popular vote and confirmed by a senate that represents a minority of Americans (the Democratic senate minority still represents 15 million more people than the Republican majority). This means that, if Trump succeeds in appointing a third justice, wholly one-third of the court will lack the democratic legitimacy of being appointed and confirmed by representatives of the people.

However, court packing also has many detractors; most significantly, Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden opposed it when the question came up during the primary debates. And this is for good reason. The term generally refers to the addition of judges in order to tilt the balance of the court in favor of the ruling party and prevent the threat of an independent court acting as a check on the ruling party’s legislative priorities and the executive’s power. This is a pattern we have seen in several failed democracies around the world, including Venezuela, Hungary and Turkey. Rather than securing democracy, court packing has served to cement the ruling party’s hold on power to the detriment of free and fair electoral competition, a fate we certainly do not want to replicate in our own institutions.

However, while court packing has its flaws, it must also be admitted that our current system is not working. The Supreme Court, intended to be a nonpartisan arbiter of constitutionality, has been drawn into the fierce political struggles of a hyperpartisan Washington. When Ginsburg was appointed in 1993, she was confirmed in a landslide vote of 96-3. That sort of bipartisanship has become increasingly difficult today, especially in regards to judicial appointments. The last two Supreme Court appointments were sources of intense political conflict — the replacement of Ginsburg has already begun to shape into another such battle. Each recent appointment has been decided on or near party line votes, a clear issue for an institution that draws its legitimacy from its supposed lack of partisanship.

From this, it can be concluded that while court packing itself may not be the answer, structural court reform is a necessity. In July, legal scholars Ryan Doerfler and Samuel Moyn set out to answer this question, arguing in their paper that rather than seeking to hide the partisanship of the Supreme Court, we should simply strip it of its enormous powers, thereby transferring more power to the people. However, in doing so, they failed to recognize the value of the judiciary as an institution in a three-branch system like that of the United States.

While the judiciary often does seem undemocratic in its removal from the people, that removal is a very intentional part of its function. The courts are intentionally divorced from the necessity of electoral competition in order to prevent them from using the sort of short-term and catastrophic thinking that many politicians do in order to secure their elections.

While a politician like Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell is incentivized to create and then break a precedent within the span of four years in order to best animate his electorate, the courts have no such burden. They can, in theory, think long-term on what is most objectively right and beneficial for the continuation of the republic, something with which the legislature and executive often struggle. If we cannot transfer the court’s powers to the legislature, then we must again return to the question of how we can reform it in order to return it to its intended lack of partisanship.

One of the best ideas for how to do this ironically requires making the court more overtly partisan. Legal scholars Daniel Epps and Ganesh Sitaraman’s “Balanced Bench” proposal is perhaps the most prominent non-court packing reform proposal, due to its embrace by candidate Pete Buttigieg in the Democratic primary. It would increase the number of justices to 15. The proposal would allow appointees to remain on the bench for life, but instead of being appointed by the current president, five justices would be appointed by each major party, with the remaining five being appointed by the other ten justices. While more overtly politicizing the appointment process, the proposal would also force a compromise in the selection of the five nonpartisan justices, theoretically increasing the likelihood of moderate justices and increasing the buffer of “swing” justices to five.

Critics have argued that the proposal would require a constitutional amendment to be put into effect, due to its shift of appointment power to the justices of the court, and that even if it were passed, overt politicization could reduce trust in the court. But while the Balanced Bench is one of the most visible proposals, it is not the only option.

Another option endorsed by Epps and Sitaraman is their “Supreme Court Lottery” proposal, which would redesign the Supreme Court in an effort to remove justice selection from the political realm entirely. The court would be composed of the 179 members of the U.S. court of appeals, with each case being heard by a random selection of nine judges. This proposal would be easier to pass into law because it does not alter the actual method of appointment, which would still ultimately come from the president and would therefore not necessarily require a constitutional amendment in order to be put into effect.

Regardless of whether McConnell and the Republican Party push ahead with their effort to confirm a Trump appointee before the presidential election, one thing has been made immediately clear by the passing of Ginsburg — the Supreme Court needs to change. How that will be accomplished is uncertain, but what I can say with confidence is that we have plenty of well-thought-out and democratically legitimate options to promote without needing to legitimize the dangerous precedent of simple numerical court packing. The Democratic Party and the left overall should embrace the idea of court reform without endorsing its most dangerous variant.

Comments ()