Harriet Washington Speaks on Racial Harm in Science and Medicine

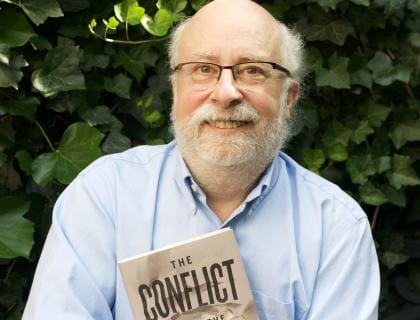

Writer and medical ethicist Harriet Washington spoke in Johnson Chapel on Sept. 30 as the inaugural scholar in the college’s Presidential Scholars series. The conversation covered topics including racial health disparities and vaccine hesitancy.

Medical ethicist and writer Harriet Washington visited Amherst for a conversation in Johnson Chapel moderated by Professor of Sexuality, Women’s and Gender Studies Katrina Karkazis on Thursday, Sept. 30. The two discussed topics ranging from racial health disparities to vaccine hesitancy. Washington, who also visited classes and met with students, faculty and staff between Sept. 27 and Sept. 30, is the first visiting scholar in the college’s Presidential Scholars series, which aims to deepen the conversation on racial history and justice.

Washington is a science writer and editor who teaches bioethics at Columbia University. Author of the acclaimed “Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present,” she also wrote “A Terrible Thing to Waste: Environmental Racism and Its Assault on the American Mind” and “Carte Blanche: The Erosion of Informed Consent in Medical Research.”

Karkazis started the conversation off by asking Washington to speak on the contemporary resonances she sees of the history she writes about. Washington responded that 19th century scientific portrayals of African Americans — which were nothing more than “the opinions of people in power cloaked in scientific data to give them a semblance of being scientifically unimpugnable” and “the embodiment of myth” — still permeate discourse on racial disproportion during the pandemic.

Suggestions that Black people are disproportionately affected by Covid-19 because they fail to social distance and are at higher risk due to personal choices to consume high amounts of alcohol, she explained, reflect the assumption that “we’re not intelligent enough to act in our own best interest.”

Washington noted later in the conversation that this assumption also underlies recent coverage of vaccine hesitancy in the nation. The dominant narrative that Black Americans are rejecting the vaccine due to wariness from the abuses of the infamous Tuskegee study, she said, is not supported by evidence. She pointed out that policies prioritizing the vaccination of the elderly and the use of online vaccination appointment systems both contribute to the lower vaccination rates among the Black population.

Moreover, Washington said that invoking the Tuskegee study to explain Black distrust of the healthcare system is ignorant and dismissive. “It is four centuries of abuse in the healthcare system, not one single study, that cause people to react,” she maintained. “This is important, because if you blame Tuskegee, you’re saying that Black people are overreacting to a single study. Black people are appropriately reacting to four centuries of abuse.”

In response to Karkazis’s question about how to change blasé attitudes toward Black and brown deaths, Washington said, “I think you have to ask that question to the people who are tolerating Black death.” She noted that she was reminded by something her mother told her and her siblings when they worried about their father’s safety serving as a military advisor in Vietnam, that “life is very cheap over there.”

“I think that this uttering about life being cheap, this vocalization of the lesser or value of other people’s lives, is something that people do very often, and I think we’re looking at that right here,” she said.

Students who attended the event expressed that Washington’s insights made them reconsider things they had taken for granted. “I thought it was a really great event to have,” said Nathan Thomas ’25. “She cleared up some of my misconceptions about things that I didn't realize I had.”

“I definitely came away [from the event] with a reminde[r] to be a critical consumer of media,” added Sarah Lapean ’23. “The narrative around vaccine hesitancy has been reported on for months and months, and I'm just like, ‘Oh, yeah, that makes sense,’ but after hearing her speak, I [realized] there's so much more going on behind the scenes than I was even thinking to look into.”

“The things that she says,” continued Lapean, “seem like things that should be obvious and yet like no one has heard about them, and so it was very enlightening.”

Karkazis appreciated that Washington drew attention to the racial harms that come from science, noting that they often “fly under the radar, because they get normalized.”

“To hear her say that we're still in the long wake and unfolding of slavery's impact on Black people in this country from a scientific perspective is an incredibly important message regarding how much work we have to do,” she commented.

Equally important in Karkazis’s view was how Washington’s points underscored the importance of cross-disciplinary training of STEM professionals in the social sciences and humanities for promoting justice in science and healthcare. She hoped that students would apply the new perspectives they gained from the talk to approach their studies in new ways.

“It's one thing to hear things like what she's saying — it's another to internalize that knowledge and integrate it into other things that you're doing,” she said. “Like, what would it mean to take that work into a class you have on biology, and think about problems with classification and categorization?”

The event certainly had students thinking in new directions, with Thomas noting that he’d be interested in taking a course on the history of medicine in the future. “It was the kind of event that starts conversations,” remarked Lapean.

Comments ()