Having Cancer at Amherst College

Contributing Writer Spencer Williams ’24 recounts his experience receiving a rare brain cancer diagnosis in 2021.

In the latter half of my freshman year, a funny feeling in my ear akin to a pulsating drumbeat led me to the Keefe Health Center. There, an owlish gentleman peered into my ear and exclaimed that I had a perfectly shaped canal. I returned to my dorm room, relieved of all ear-related anxieties.

That finals season, I took much longer than usual getting my exams in. When summer finally came, I rested for an initial month. Then I started working the three jobs I had lined up for the stretch leading into the 2021 school year. After my shifts, I would fall into bed and sleep for hours. I do not remember thinking that anything was wrong. I do not remember thinking much at all.

In the fall semester of my sophomore year, I was slated to arrive at Amherst College one week early for Community Advisor (CA) training. On the day of my flight to college, I projectile vomited all over the living room. My mother brought me to the ER, where I was diagnosed with an ear infection.

When I arrived on campus, I stopped functioning. I missed CA training sessions; I failed to speak articulately; I passed out in the dorm rooms of the Asian Culture House. To say that I shut myself into my dorm room would require intent on my part. In truth, I could not muster the strength to get out of bed in the sweltering heat. I texted my friends to bring me food from the cafeteria. They were told that it was against school policy.

I tried to get help. Once again I went to the Keefe Health Center. The nurses there took away the antibiotics I was taking for my ear infection.

The first time the ambulance was called on me, I threw up in the waiting room of Cooley Dickinson. I tried to speak to someone at the front desk. In response, they gave me a pail. I waited for hours. The doctor saw me for 10 minutes and discharged me with Tylenol. I was then stranded at Cooley Dickinson in the dark. I called my friend for help and he attempted to contact our supervisor, Alyssa Carlotto, who replied that she was off work. Finally — I do not know how or when — someone from Amherst called and informed me that Exclusive Car Services would be ferrying me back. I sat outside in the dark and waited while my head felt like it was being smashed by a hammer.

The weeks passed in a haze and classes began. I attended none of them. One day, I somehow wandered into the common room. My friends saw me and called the ambulance again. By then, complete aphasia had set in: I could not speak. Strapped to the stretcher, I texted a photo of my feet to my parents. The EMTs asked me questions I could not answer.

To this day, I remember what one of the EMTs said to a nurse at Cooley Dickinson when we arrived: “He can’t speak English. He’s mentally slow and inarticulate.”

I tried to object. I tried to tell them that I was a student at the college. I opened the notes app on my phone and attempted to type. I strained to scream, to cry out, for help. Nothing. I could not make a single sound. I was trapped in my own mind, in excruciating pain, as the medical staff who were supposed to help me brushed me off as an idiot who did not speak English because I am Asian.

It is perhaps a relief that I do not remember much of that night.

I woke up in Massachusetts General Hospital. My parents, who had flown in from Oregon, were by my side.

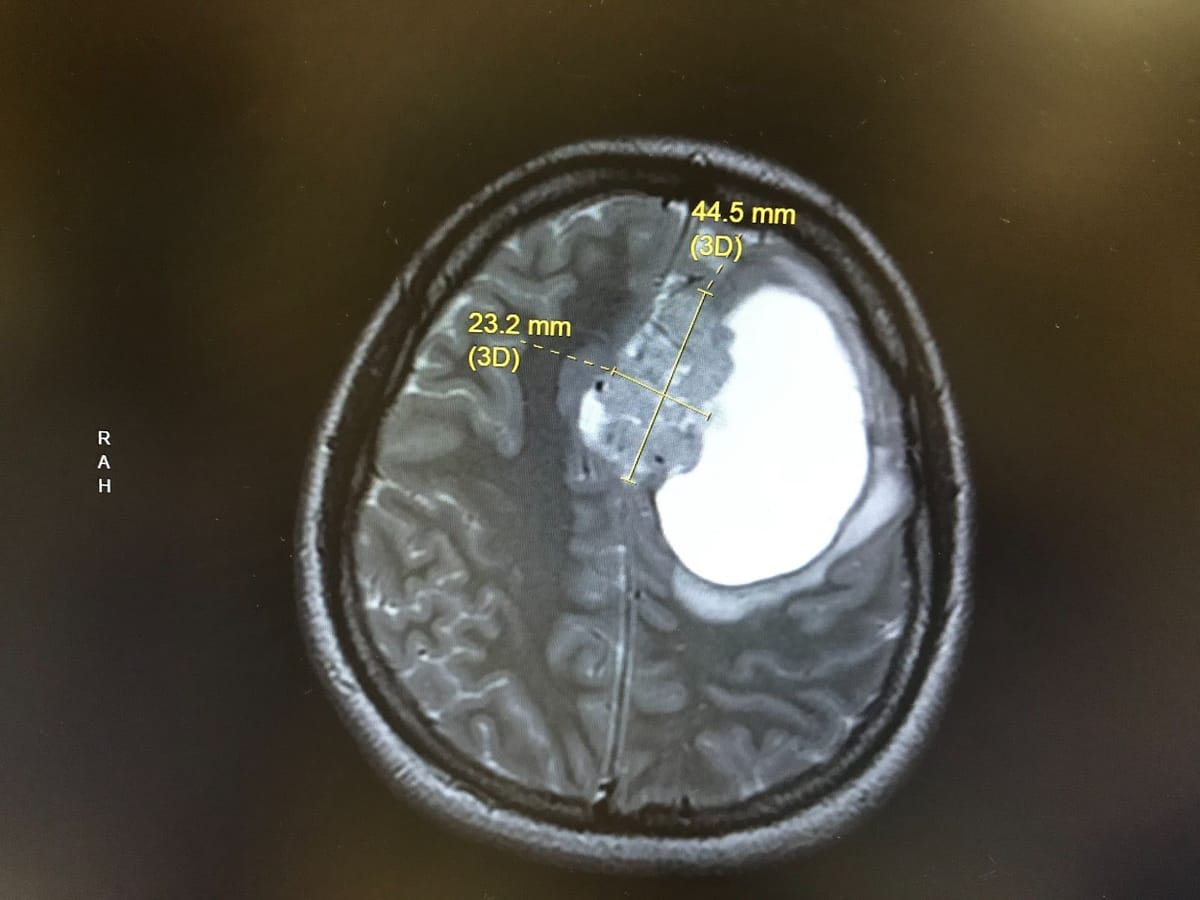

The night before, my mother’s desperation had saved my life. She had called and called my phone until a passing nurse finally noticed. My mother had frantically explained to her that I did, in fact, speak English, and that I was neither mentally slow nor inarticulate. During the subsequent CAT scan, the nurse had seen the tumor that eclipsed greater than a quarter of my brain. She had flooded me with steroids to reduce the swelling and sent me off to a more capable hospital.

If someone had not noticed, I would have had an aneurysm and died.

My consciousness vacated my physical body for the week before surgery. I did not know where I was; I did not know what year it was; I did not even know my own name. There are massive gaps in my memory up until the 11-hour brain surgery, but I recall passing flickers of little light in the swelling, tumorous dark.

This is what I choose to remember: My mother spooning cool, sweet watermelon onto my tongue. Two friends crying and stroking my arm as I tried and failed to form words in my hospital bed. My debate coach talking at me because he understood that I could not talk back. So many people sending concerned messages, well wishes, and desires to visit me. Professor Sarat, who taught my first-year seminar and who has also experienced cancer, comforting my crestfallen parents. My nurse cradling my head and whispering that she would put me at the top of her prayer list. My stepfather pulling me into a gentle bear hug as I cried over the uncertainty clouding my future. FaceTiming my grandmother and her sobbing upon seeing that I was alive, alive, alive. Finally, right before the sedation set in, my neurosurgeon giving me a high-five.

There is a sword that hangs over my head. Its name is grade 3 anaplastic ependymoma, and it is a rare brain cancer that will follow me for the rest of my life. I have had three brain surgeries, 39 sessions of radiation treatment, and months of chemotherapy since I took medical leave. I have experienced the restless aggression of steroids, the nausea of bitter-tasting chemotherapy medicine, and seizures that render my entire body helpless. I have had more near-death experiences than I can count.

But I choose to focus on the overwhelming kindness in my darkest moments and I weep with joy. Cancer is a sword, but it is also a reminder of human kindness, of soft touches and quiet connections. When I die, whether that be in five years or one hundred, may I have lived tenderly and lovingly, fluffy with empathy and heart. Amid the genetic mutations and surgery scars, there is an undeniable beauty that traces the preciousness of my single human life.

This I have learned: During a burial is when the flowers come.

Comments ()