Memories and Nostalgia in A24’s “Aftersun”

Charlotte Wells’ new film “Aftersun” is a visual representation of the cracks in our memories. Cole Warren ’24 reviews the movie, which follows a daughter reflecting on her father’s death upon becoming a mother herself.

There is always a certain sadness in nostalgia. The nature of the memories doesn’t matter — whether happy or sad or impactful or minute, they are always a fleeting interpretation of a past that you will never be able to experience again. As you age, everything you’ve lived through begins to amalgamate or just fade away, leaving only distinct images that bounce around your skull as you try to go back in time. Memories are so emotional because they are so imperfect, perpetually incapable of returning us to all those moments we want to relive. It is this pain of remembrance that the film “Aftersun” captures so well, illuminating all the complexity of reminiscing about the places you will never revisit and spending time with loved ones who you can never see again.

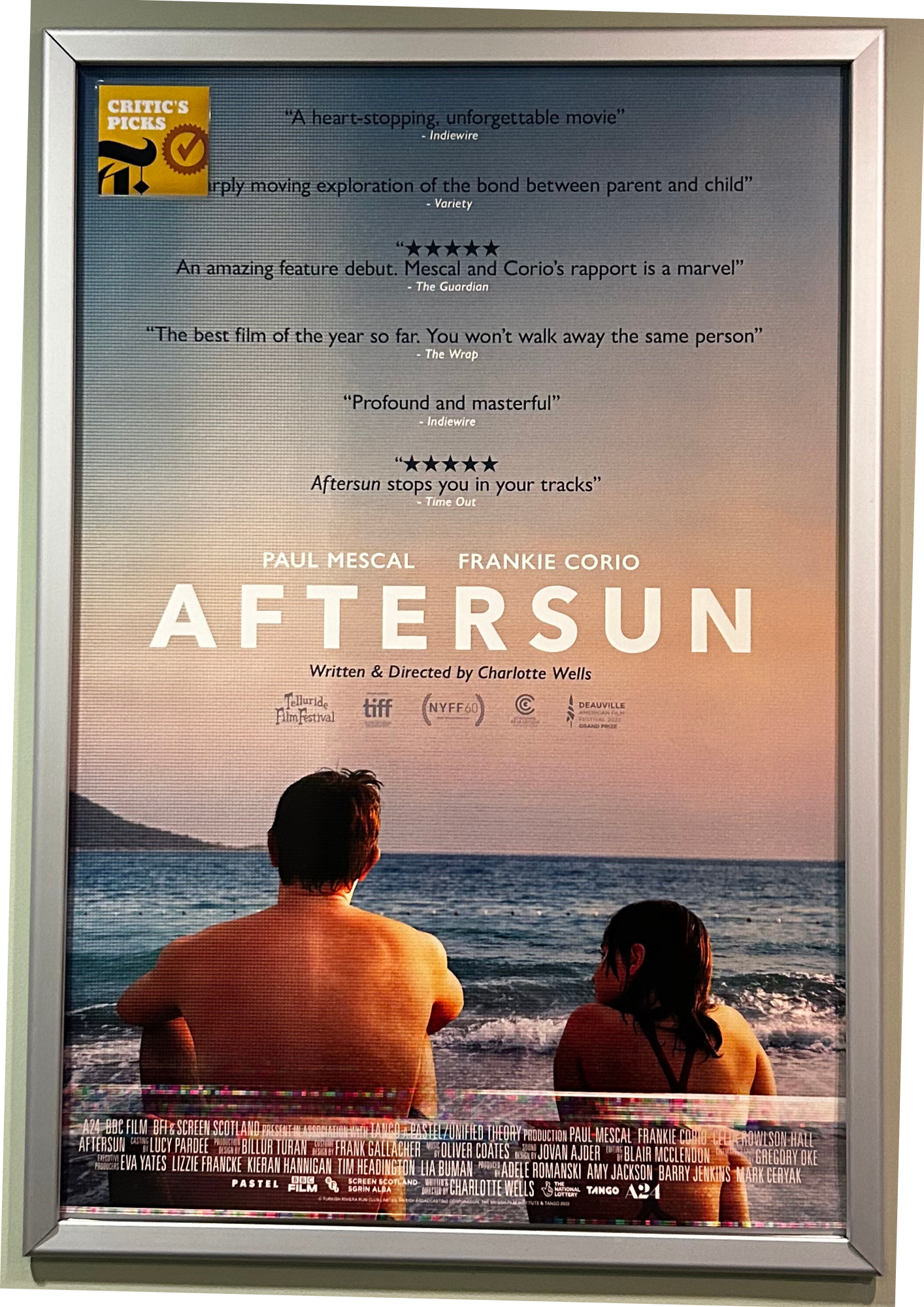

If you have only seen the poster for “Aftersun” or heard a brief description of it, you may be inclined to think that the film is just another one of the standard indie dramas that appears every time award season rolls around. When I first heard about it, I chalked it up to being another movie about an unhappy family, this time exploring the tense relationship between father Calum (Paul Mescal) and 11-year-old daughter Sophie (Frankie Corio) as they vacation in a Turkish resort town. However, viewing “Aftersun” in that light is a great disservice to the uniquity of writer and director Charlotte Wells, whose debut feature undertakes the task of portraying the anger and confusion surrounding grief without resorting to melodrama.

What makes “Aftersun” stand out is the fact that the film itself is the memory of an older Sophie (Celia Rowlson-Hall), who is now both a parent and the same age her father was during their fateful vacation together. “Aftersun” is a visual representation of memory, depicting the minutiae of their vacation, all the while being intercut with brief scenes from home movies and harrowing shots of her father in a strobe-lit nightclub. As the film progresses, the line between fact and fiction blurs and becomes fundamentally unimportant. The movie transitions from tender moments between Sophie and her father at the beach to a fictional nightclub, where an older Sophie screams at the image of her dad. By this point, the audience begins to infer why these two seemingly unrelated settings are connected; they are adult Sophie’s memory, in all its joy and anger, of the last time she ever saw her father alive.

Probably the strongest part of Wells’ writing and directing is that she never feels the need to delve into exposition for the sake of clarity. Because the film centers on Sophie’s perspective, we are isolated from Calum’s struggles, never fully knowing why he appears in crisis throughout the vacation. Rather, all we see are the little moments of tragedy in Calum’s life: his deprived youth (he became a parent when he was only 19 or 20), his failure to form relationships, his impulsive purchases of souvenirs he can’t possibly afford, and his self-destructive behaviors resulting in new bruises or scrapes that he brushes off to Sophie. The few moments of actual conflict between Sophie and Calum, such as when he refuses to sing karaoke with her, are quickly resolved for the sake of the vacation. Wells captures best how parents often hide their flaws and failures from their young children, and that is how we are forced to see Calum: His life, struggles, and personality when he is not acting as a parent are all left to the viewer’s imagination.

However, despite the intelligence and emotion in Wells’ screenplay and direction, the film’s emotional core is secured by the performances of Mescal and Corio. Both are relatively new actors on the silver screen, and maybe it is because of this that they seem so realistic. Their conversations are natural: They are bored with each other, make each other laugh, and occasionally quarrel. Yet they always feel like real people, and the audience can immediately recognize in their acting a familial relationship. Mescal and Corio overcome one of the most demanding challenges of acting: making the viewer forget that they are even actors at all.

“Aftersun” is a film that will linger with you long after you leave the theater. The movie’s juxtaposition of heartwarming and heartbreaking scenes is emotionally devastating and surprisingly personal. Whether you have lost a parent or a loved one, or even just experienced the contradictions of emotions from past memories, “Aftersun” is a film that visually represents the tragic beauty of reminiscence.

Comments ()