Ora Szekely Discusses What We Do and Don’t Know About the Israel and Hamas Conflict

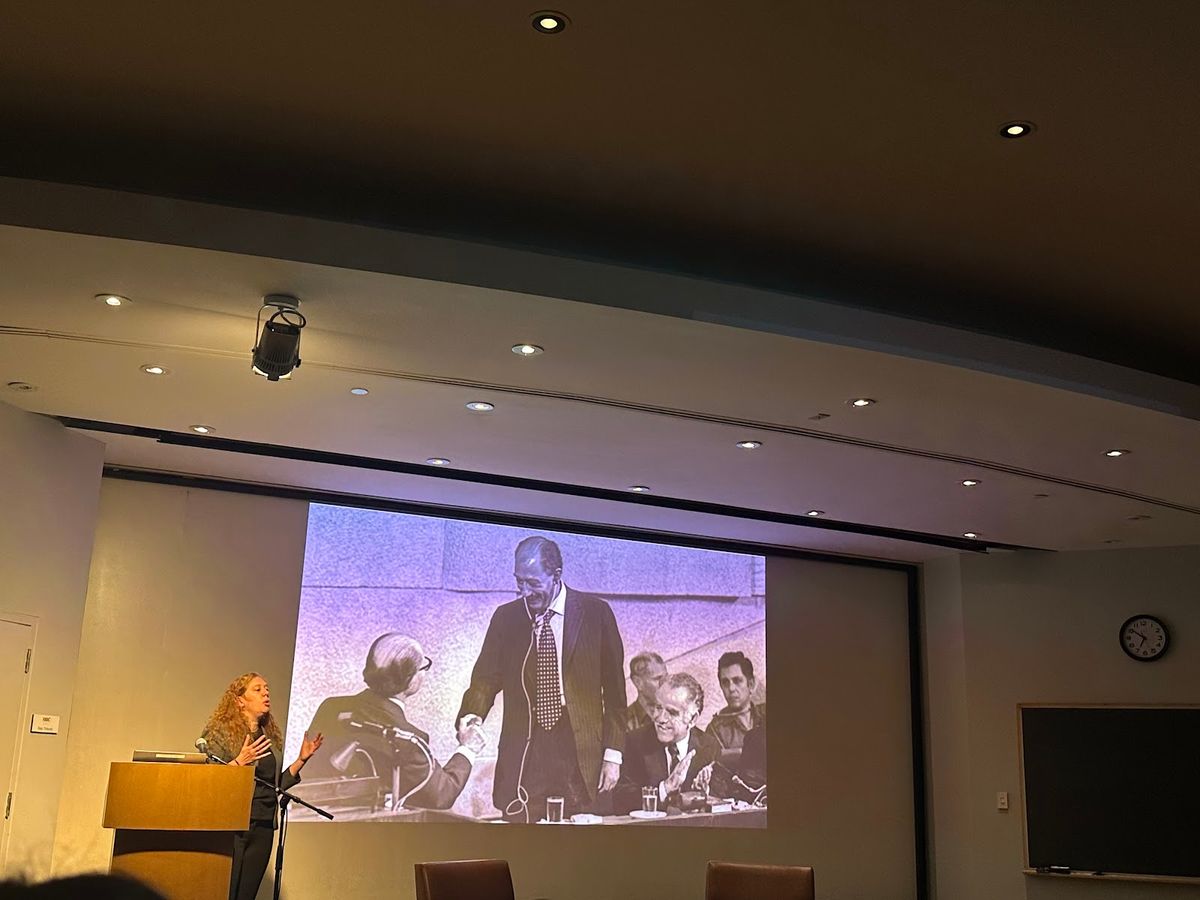

Ora Szekely, associate professor of political science at Clark University, explained the historical context of the Israel and Hamas conflict, and provided an explanation of current events at a talk on Nov. 2.

Ora Szekely, associate professor of political science at Clark University, gave a talk on the violence between Israel and Hamas in a full Stirn Auditorium on Thursday, Nov. 2.

Szekely, whose research focuses on the policies of nonstate armed groups in the Middle East, began with a recap of what has happened since Hamas’ attack in Israel on Oct. 7, with the goal of getting the crowd on the same page. She explained the historical context, provided reasoning for why Hamas launched the attack, explained why Israel responded the way that it has, and concluded by giving some ideas for what comes next.

Sheree Ohen, chief equity and inclusion officer, gave the opening remarks to introduce Szekely for her talk, which was titled “Israel and Hamas Conflict: What We Know and What We Don’t, explaining that the decision to invite Szekely was driven by a sense that students on campus had a desire to “better understand the issues and convictions related to the many Israeli and Palestinian perspectives.”

The college is seeking input on the list of speakers “from a variety of sources, including faculty, staff, and students, with the goal of bringing diverse perspectives on campus,” Ohen said.

Szekely began by discussing the conflict’s background, highlighting that “it’s a profoundly modern conflict that dates give or take [to] the 19th century.”

Israel occupied Gaza after a war in 1967 and from this point “there is no longer as much conflict between Israel and the Arab states, but rather asymmetric conflict between Israel and Palestinian non-state armed groups, mostly with the Palestine Liberation Organization,” Szekely said.

In 1988, Hamas was founded and “immediately became a really important political and military actor.”

In 2005, Israel unilaterally disengaged from Gaza, pulling out previously-existing Israeli settlements and removing its military forces. Even when this occurred, Israel still “retained control over Gaza’s borders by land and sea with the exception of a small piece of Gaza which borders Egypt.”

Hamas won the Palestinian Authority Legislative election the next year against Fatah, and there have been no elections ever since. Since then, Szekely said, Gaza has been “blockaded by Israel, both by land and sea, with the cooperation of Egypt, which has led to truly terrible living conditions for people in Gaza.”

In speaking about the motivations of Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack, she acknowledged that “one answer is that this was driven by regional politics.” It was “Hamas’ attempt to make it impossible for any other states to decide to make peace agreements with Israel, and to also create a sense of urgency around resolving the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians that hasn’t really been there in recent decades”

Another possible motivation for the attack is to enable Hamas “to take control of the internal political conversation within Palestinian politics.” This is due to the fact that Hamas is not popular in the eyes of the Palestinian population, she said. When Palestinians were asked “who do you think has the right to represent the Palestinian people?’ 24 percent said Hamas, 27 percent said Fatah, and the largest group said neither.”

As for Israel’s response to the attack by Hamas, Szekely said there are “a lot of possible answers”

The first explanation is that “the purpose of the response is to remove Hamas from Gaza. Szekely noted, however, that attempting to remove Hamas as a “political leadership entirely.”

“[It] is difficult to imagine how this could be fully accomplished,” she said.

This is because “much of Hamas’ high-level political leadership is not in Gaza, they are mostly safe somewhere else, possibly in other countries in the region.”

A second explanation is that Israel is sending a message to “reestablish deterrence.”

“It is entirely realistic that the IDF [Israeli Defense Forces] may feel the need to prove to Hamas, to the Israeli public, and also to anyone who is watching that they’re still able to attack their enemies,” she said. “Also, that any attack on Israeli civilians will carry a terrible, terrible price. That price is currently being borne by civilians in Gaza.”

A third explanation rests within “internal political divisions,” in Israel.

Szekely then moved on to discuss what comes next. “There is a chance that one of Hamas’ allies may become involved in the war,” she said. It’s not clear if these allies, such as Hezbollah, “have any interest in a wider war.”

“Israel has also signaled that it doesn't want a two-front war. However, even if neither side is interested in a full-on war, they might get one anyway”

The other possible scenario is that Iran gets involved. If this happens “it is very easy to see the United States deciding that it then needs to get directly involved as well.” Szekely said this chain of events is unlikely.

She emphasized that the geopolitical effects won’t be restricted to military action. “Even if we don’t see larger military escalation, we will see political escalation across the region. Especially in countries that have peace treaties with Israel,” Szekely said.

Szekely illustrated what she sees as the two possible conclusions to the war. The first is that Israel reduces or even displaces Hamas’s governance of the region, which would open a power vacuum to be filled either by a new or old ruling entity.

The other path is more hopeful. “There are a lot of examples in history of truly horrific wars which were eventually transformed and ended because people simply chose to do something different,” Szekely said. Though the future is uncertain, Szekely lingered on the idea that “maybe this time history ends right side up and things are better than they found them.”

Following the talk, there was a Q&A session hosted by Associate Provost Pawan Dhingra.

One student asked, “What could be a way of resolving this particular conflict?”

Her answer emphasized “taking seriously what people in the region want, not what either self-interested political leaders or people on the outside think that they should want.”

Students who attended the talk said they were impressed by Szekely’s presentation of the politically charged issue without increasing hostility.

Harrison Blum, director of religious and spiritual life, commented on the power of Dr. Szekely focusing on the personal impact on people. A post-talk dinner with Szekely included Jewish, Muslim, and Middle Eastern students, along with political science majors. The conversations during the dinner were “thoughtful, curious, and humane,” said Blum.

Blum ended with a message of hope.

“Dr. Ora Szekely's talk, and more like it, will bring fact-based and multiperspective voices to deepen our historical understanding and present moment empathy,” he said.

Comments ()