#ReclaimAmherst and the Promise for Change

“Black people are the condition of possibility for the existence of Amherst College.” From its opening lines, the campaign to #ReclaimAmherst makes clear the legitimacy of Black people’s claim to the institution. From the college’s founding years to Amherst’s current status as a leader in diversity, Black people have always propped up Amherst College, the document argues.

On the heels of #IntegrateAmherst, the @BlackAmherstSpeaks social media campaign — which has gained over 3,000 followers — and a national awakening on race turned inward, #ReclaimAmherst is a thorough 16-pages of text that channels those energies into a clear, concrete outline for change within the college.

Kyndall Ashe ’18 and Haylee Price ’18, who created and run the Black Amherst Speaks Instagram account, and Jeremy Thomas ’21, the Black Student Union’s (BSU) campus and alumni liaison and former president, are the driving force behind the project, which is a collaboration between the two groups.

The campaign outlines a broad set of priorities for the college to make in order to nurture a campus environment that is beneficial and responsive to its non-white students — Black students, in particular — who give to the college much more than it gives in return, the document writes. On its webpage, individuals sign on in support and pledge to withhold financial contributions from the college until priorities are met. Already, the campaign has over 400 signatures, most from students and alumni.

The document asks the college to deliver on its principles. It posits the question of how Amherst can move forwards with its core values of liberal arts thinking while correcting the ways that those very same values have worked to sideline and oppress minority groups. Most of all, it lays out the foundation to make these values work for the people who make up the institution — the work of “reclaiming.” Each section closes by stating “We are Amherst. We demand Amherst.”

“It’s a way to reassert ourselves as part of the institution,” said Thomas. “[President] Biddy [Martin] isn’t the institution. She’s the custodian of the institution; she’s supposed to look after its best interests, but at the end of the day, we are the institution. All of us are.”

The introduction concludes by saying “We want our institution. The whole thing.”

Reclaim Amherst outlines priorities for change in six distinct categories: 1) a clear value statement, 2) diversity in leadership, 3) “the wages of Amherst,” which outlines pathways to make resources more accessible to everyone and for the college to use its funds towards uplifting Black people, 4) health and safety, 5) proactive learning on anti-racism action and, lastly, 6) apology and reparations.

“We’re trying to make it more of an outline or a guide, than demands. I feel like at this point, we’ve demanded. If the administration doesn’t want to do it, that’s up to them. That says more about them than [it does about] any of the students who go through the school,” said Price. “We’ve done so much unpaid work to prove here are all of the things that can be done.”

That list of what can be done is a long one, and Reclaim Amherst aims to create a robust starting point that brings together the diverse, disparate range of what needs to change across the campus. Such guidelines include divestment from private prisons and fossil fuels, disarming the Amherst College Police Department (ACPD), the creation of an Asian American Studies department and educational trainings for all faculty and staff. The full list of Reclaim Amherst’s proposals can be found at the end of this article.

“These are things that should just be natural in a sense. It’s just us trying to get the experience that we applied for, resources are used for, basically so just that everyone can experience Amherst in the best way possible,” said Price. “We should be set up in the best way, to do the best work that we can while we’re there and once we leave, as well. It’s really just almost kind of a no-brainer. There really should not be a debate as to why [the changes are necessary],” said Price.

Missing from this exhaustive explanation of changes are any lengthy descriptions as to why these points are specifically salient. But to Ashe, Price and Thomas, that’s not the job of Reclaim Amherst; that’s where Black Amherst Speaks, and the deeply personal first-person accounts of encounters with racism that it highlights, come in.

“I think that’s why that partnership [between BSU and Black Amherst Speaks] formed really well,” said Ashe. “The stories that represent a lot of the systematic and institutional issues that we know exist [work] almost as a backing for building on a lot of demands that have already been created in the past.”

“I’d been told by professors before ‘Oh you know, people don’t get it.’ Some people or some professors or some administrators think that going to Amherst and being unhappy is a choice because it’s so diverse. A lot of the questions that we got [in a recent, remote faculty meeting where BSU presented on #IntegrateAmherst’s progress] were like ‘Can you talk about racism?’ ‘Have you ever experienced racism? and what is that? and what does that look like?’” Thomas said. “So seeing Kyndall and Haylee doing this awesome work, I was like ‘This is perfect!’ I had said at the beginning of the meeting — at the very beginning of that meeting, which is why those questions were so frustrating — was ‘no one is here to prove racism to you.’ That’s not what I’m doing; that’s not what I’m interested in wasting my time on. So to have these stories [on Black Amherst Speaks], as people are like ‘oh wow bad things do happen.’ Yeah they do!”

The document does make significant allegations to explain the need for some changes, though. The first being Title IX’s “racist, homophobic, and transphobic” practices that have systematically harmed Black students who seek help from the office. The organizers further elaborated to The Student that the office’s composition of entirely white, straight, cis-gendered white people sways its perspective and creates the impression that it treats incidents between non-white, non-heterosexual individuals more as “sexual deviance.”

Additionally, it cites that the Office of Financial Aid consistently short changes students from marginalized groups, as understood through collective individual experiences with the office throughout the years. Its similarly majority-white office precludes it from “delivering news appropriately” to non-white aid recipients or “advocating for change where they see it possible,” the organizers felt.

Regarding these statements, the Office of Communications wrote that “the charges that are directed at individual offices have to be dealt with separately by seeking more information from those who have been negatively affected and are willing to talk with us about the appropriate way forward.”

The office also added that the administration soon plans to work towards the priorities Reclaim Amherst outlines: “We have seen, read and discussed Reclaim Amherst. Over the summer we have been discussing how to accelerate efforts to be an actively anti-racist college. President Martin will soon send out a letter and key elements of a plan. We believe it addresses a number of the issues that Reclaim Amherst raises and will be a living document as discussions continue.”

Similarly, the Association of Amherst Students (AAS) pledged its support for making the changes within Reclaim Amherst in an email sent to all students on Wednesday morning, writing “We must take action to make Amherst a place where everyone is valued and can prosper. AAS stands in full support of this movement. Change can only happen when everyone gets involved.”

The language that Ashe, Price and Thomas use to express Reclaim Amherst’s priorities reinforces their necessity, in a forceful yet quiet way. They do not write that they “ask” or “demand” these changes from the college; they do not urge the institution that it “must” make these changes; instead, they simply write “this will change” and they college “will” act accordingly. It’s a subtle way of asserting themselves as part of the institution.

“The language of ‘will’ — ‘the college will do these things’ — is different than ‘we demand’ or ‘the college must’ or all these things. If [it does] not [do this], you’re making a choice, and that choice is going to be noted, by us, by alumni, by future students, by prospective students,” said Thomas. “I think what that does by reframing that, not as a debate but as a choice, says that ‘you can make this decision, but it’s going to have consequences.’ I think it’s bringing those consequences to the light.”

The document builds on a long past of asking for change that comes up short each time, felt most recently just this spring in the wake of racist hate speech from white men’s lacrosse athletes.

“It does feel like many folks at the school right now are not only willing to listen to the voices of students of color, but are eager too. I feel this is in part driven by the nasty sickness the events of this spring with the men’s lacrosse team revealed themselves to be a symptom of, but also because of what is happening in this country and the current reckoning with what has been happening in this country for the past four years, the past forty years, and for every year since this country was first brutally colonized by the oppressive and destructive hand of whiteness. I hope this feeling is not just that, and that the tragedy we have seen this past summer and for centuries, both in this country and at Amherst, becomes the turning point we so desperately need it to be,” said Bella Edo, the president of the Council of Amherst College Student Athletes of Color (CACSAC), who helped contribute to the document’s section on athletics on behalf of CACSAC.

The language of “will” in the document also underscores that the “campaign aims at what we need, not what it would be nice to have,” as the document writes.

“[It is also a] function of making yourself a reminder to the institution: that we are the institution; we are a part of the institution; and that these decisions don’t get to go made or unmade without our voice and without our input,” Thomas said.

Price echoed Thomas, adding that the college should use Reclaim Amherst to look inwardly for change. “We’re trying to do stuff, that they have a lot of smart people who they pay a lot of money in the administration [working on]. We’re kind of out here putting out some big ideas that can only help [the school],” she explained.

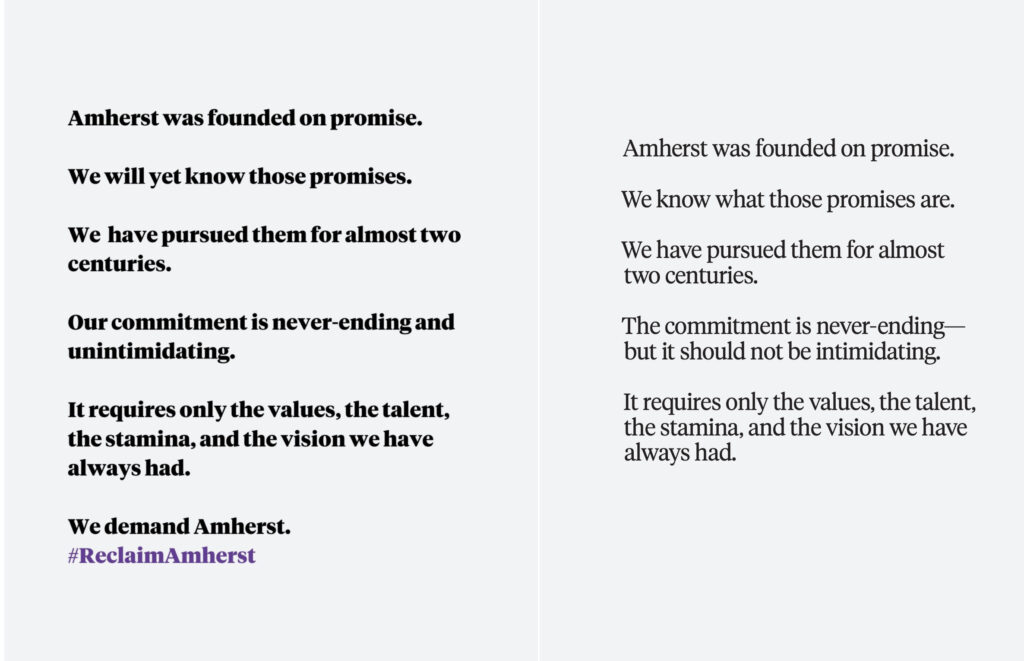

The document closely mirrors that of Amherst’s Promise Campaign, the fundraising effort launched in honor of the college’s bicentennial. These echoes include the subtle borrowing of language, slightly altered: “Amherst was founded on promise. We will yet know those promises,” the Reclaim Amherst pledge writes, shifting the Promise campaign’s language that “we know what those promises are.” The heading titles are a direct copy of those the Promise campaign put forth. It’s a subtle touch that drives home the organizers’ message that the college’s core values are “just as important as they always have been,” yet they are unfulfilled.

It also answers the question, Thomas explained, of “What documents are there? How do we write ourselves into the history of the college?”

The question of history — whose is preserved, whose is illuminated and whose is ignored — is central to the group’s mission. It strives to bring forth the history of Black people at Amherst and make sure they remain part of the history, for generations to come.

For the BSU writ large, “our participation in #ReclaimAmherst is to ensure that as our school enters its next 200 years, Amherst takes deliberate and sustained action to create the campus it has always promised, where Black students, as much as any other, can thrive,” wrote Ayodele Lewis ’21, BSU’s Junior Chair, and Zoe Akoto ’21 BSU’s Secretary, in an official statement from the group. “As we approach Fall 2020, an unprecedented semester, the BSU looks to work with the college to see Amherst’s promises fulfilled, finally and with haste. As the late John Lewis championed, we cannot accept gradual racial change, and as institutions nationwide are quickly reckoning with their history, for Amherst to defer confronting its own is unacceptable. Entering the fall, our focus is not only on the next 200 years, but on the uncertain one ahead of us as we welcome the Class of 2024.”

Where Promise closed with a letter to the Class of 2021, the bicentennial class, #ReclaimAmherst writes to the class of 2071. “In fifty years time we hopefully have a document and a record to say this is what happened this long ago. Having a record that goes beyond us and goes beyond this administration. It is a good marker for future generations and future leadership to have a gauge,” said Thomas.

Much of the project pivots between looking to the past and towards the future; the document rests on this understanding of how the history of Black people at the college shapes — and will shape — what lies ahead for other Black students. Black Amherst Speaks hosts a series called “Fact Fridays,” that feature excerpts of Black Amherst history. “Fact Fridays are the first time I’ve ever seen the college’s [Black] history promoted or put out in any way that’s substantive and thorough,” said Thomas. “Seeing that for the first time was super invigorating. ”

For Ashe, who helps curates the posts, “To me that is so refreshing.” But, it is more than that; it’s a reminder that this struggle for equality at the college “is not new.”

When Ashe was a student on the President’s Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion, “A lot of the frustration was on why are we reinventing the wheel or acting as though the demands or the ideas we have are new — they’re not.” In Reclaim Amherst, new changes reside alongside outlines for improvement that have existed for decades. The organizers cited drawing from the Uprising Demands, created during Amherst Uprising, from Chaka Laguerre 08’s letter and from Afro Am Society Demands of 1969.

“[Black Amherst Speaks] is backed up by a lot of alumni, going back to the sixties,who have actually seen it or heard of it and said, ‘this was happening when I was there too. I can’t believe this is still the case.’ It’s really interesting to have those dots being connected across history,” Ashe explained.

However, parts of the history the campaign highlights are muddied. The opening lines of the document states “the founders of Amherst College were slave owners,” and later, the document specifically cites Rev. David Parsons. Mavis Christine Cambell, in her book “Black Women of Amherst College” explains that Rev. David Parsons was one of the 12 slave owners identified in Amherst in the mid-18th century, and he used his slaves to tend to his land and even run his tavern. Their names were Pompey, Rose and their son Goffy. Yet as Mike Kelly, head of archives & special collections, pointed out, Parsons died in 1781, forty years before the college’s founding, and there is no known record as to whether upon his death, Parsons freed his slaves or passed them on to his son.

Kelly hopes that the Archive’s record book for the First Church of Amherst that covers 1734-1819 will soon hold more answers. It’s Parson’s son, confusingly also named Rev. David Parsons, who is among the college’s founders, as an early big donor (of both land and money) and president on Amherst Academy’s Board of Trustees, according to both Kelly and Campbell.

Famously, he attended the laying of the at cornerstone South Residence Hall, which “was meant to mark his retirement from Amherst Academy and the passing of the torch — Noah Webster took over as President of Amherst Academy in 1820,” Kelly explained. It’s worth noting that Webster was a staunch abolitionist and co-founder of the Connecticut Society for the Abolition of Slavery, according to Kelly.

When he died in 1823, he left behind a large fortune, yet no information regarding Pompey and the other slaves, perhaps indicating they were no longer in bondage at the time of his death or that he ignored them altogether. “We will need to do more research to see if [Parsons] also kept slaves, but it seems unlikely,” said Kelly.

Though less direct, the influence of slave labor is still embedded in the college’s founding: “The Parson’s great wealth (father and son) was enhanced by slave labor, facilitating the son’s contribution of $600 initially to the permanent Charity Fund that established Amherst College, then Blacks in this country could safely claim to have contributed to the establishment of the college — even if indirectly,” wrote Campbell.

Kelly also pointed to Colonel Israel E. Trask, a Trustee of Amherst College from 1821-1835 and owner of a slave plantation in Mississippi. Deputy Archivist Chris Barber compiled a biography of Trask, and her research is included in the Archives finding aid. He built one of the first cotton textile factories in Western Mass and continued to run his Mississippi plantation throughout his life. He made only one relatively small pledge to the college of $500. Barber writes “If President Edward Hitchcock can’t say what Trask did for the college, he probably didn’t do much.”

It’s clear, from the research and reparations to the institutional overhaul Reclaim Amherst outlines, that this is just a starting point for campus change. It’s one with momentum that goes beyond the Black students on campus, too. “To me, this is so easily something that can be applied to so many different groups. We did it because its this moment, this is our identity,” said Price.

To create the document, the organizers collaborated with the Native and Indigenous Students Association (NISA) to include language on the land acknowledgment, with the Asian Student Association to build in priorities around the Asian American Studies major and CACSAC to develop the sections on race in athletics.

“Although the action items center Black experiences, action items such as creating more mental health services for BIPOC, having more Black professors with tenure, and recognizing the colleges’ history, will benefit and pave the way for other communities of color on campus. For example, it may be possible for more Native and Indigenous professors may be hired and given tenure,” said Nicole Vandal ’21, the former co-president of NISA. “I think most of the changes I would like to see are the same as our Black sisters, brothers and siblings. Throughout history, Black communities and Indigenous communities in what is now called the United States have fought together against oppression and all our struggles are interrelated.”

“Any step towards accountability and representation on a higher level is a good one for [People of Color (POC)] on campus,” said Sunghoon Kwok, the ASA member who collaborated most closely with the organizers of Reclaim Amherst to include the provision for the Asian American studies major. “Obviously there are other pinpoints for Asian students on campus that we would like to be addressed, but for the most part, the document outlines a lot of things that are wrong for all POC, mainly addressing Black students. But I think everyone will benefit from these changes. We understand the urgency and prioritization of Black students on campus.”

Kwok believes that this momentum behind intersectional priorities will help fuel Asian student activism in the semesters to come: “I hope this will invigorate the Asian students on campus. I really hope that we ride this momentum and create an identity for Asian students on campus and really take time to detail out the problems that we face as Asian students,” he said.

“We have passed a point of no return and what we previously viewed as ‘normalcy’ is no longer an option. As a result of the pandemic, as a result of the social and political realities we find ourselves in, we can longer tolerate incremental shifts. We need an upheaval and we hope to capitalize on this time as we pursue our own initiatives and support our fellow affinity groups as we are all trying to make things better for all of us,” said Edo. “It definitely feels like a moment where the things that have traditionally stood in the way of change are starting to give. This time feels unique not in the devastation and pain that it holds, but in that it truly feels like the atrociousness of what happens to black and brown people in this country is causing many faculty, staff, administrators, etc. to take hard looks at what they have allowed that perpetuates systems of oppression and how they perpetuate those systems themselves at Amherst.”

Reclaim Amherst’s authors are also hopeful that this is the moment to break the pattern of racism that Black Amherst Speaks chronicles across generations.

“Arundhati Roy gave an interview, where she said ‘the pandemic is a portal.’ [She explains that] historically that has been their function. it forces you to sit and imagine the next world, basically, because the world that we’re living in is clearly not sufficient because we see all the different ways that current infrastructures are failing. You have to go forward in a different way than before,” Thomas said, dropping the link to this interview in the chat of our Zoom box. “So this is our way of saying, No, we don’t want to return to the past, where all these things are not great and happening in this way. We want to go towards a different version of the future where things are happening differently.”

What #ReclaimAmherst will change:

The college needs an institutional value statement that condemns racism and discrimination.

The Board of Trustees needs two Black student trustees on the board. A Black professor will take over as Dean of Faculty, while the current Dean of Faculty and Provost, Winkley Professor of History Catherine Epstein, will continue on as Provost. Administrators must participate in anti-racism training, and the overwhelmingly white bodies of the faculty and high-level policymakers will diversify. It outlines the need for an audit of governance committees at the college.

Exclusionary expenses like textbooks, printing, and laundry detergent should be free, and buildings should be accessible. The process of granting tenure must be transparent to weed out biased decisions that create the racial disparity in tenured professors. The college must divest from private prisons and fossil fuel companies. The budget of the Office of Diversity and Inclusion must increase, and the donation-matching fundraiser, Amherst Acts, needs to be annual.

The Amherst College Police Department (ACPD) cannot carry firearms, and must scrutinize its use-of-force policies. Any law enforcement besides ACPD should not set foot on campus.

The demographics of college counselors need to align with students’, and to reach that, the Counseling Center should hire two Black counselors and a Black psychiatrist.

College handbooks and faculty and employee contracts will include anti-racist policies.

Educational trainings across campus, for students, staff, faculty and administrators, all must center bias, implicit bias, and bystander intervention, and every major’s requirements need to include one class on the “salience of race within their chosen discipline.” Every department needs Black faculty and faculty members of color.

Asian American Studies must become its own department, at last. It’s a development that the Asian American Studies Working Group (AASWG) has been advocating for since 2015, with the stated goal of establishing the major by 2025.

The college needs to have an annual report on racial and socioeconomic report, the first of which must illuminate the past 50 years of college history. Then, the college needs to act on the data that the report brings forth.

The document outlines the need for a sincere reckoning with Amherst’s racist history. The school needs an official land acknowledgment to be read at major events, marked clearly on the website and on-campus sites — the college sits on Nonotuck land. The Five College Native American and Indigenous Studies webpage shares suggested language and history of how to acknowledge this: “I’d like to begin this event by acknowledging that we stand on Nonotuck land. I’d also like to acknowledge our neighboring Indigenous nations: the Nipmuc and the Wampanoag to the East, the Mohegan and Pequot to the South, the Mohican to the West, and the Abenaki to the North.” In an interview, Vandal said, as Reclaim Amherst writes, that “a land acknowledgment does not repair the long history of genocide and oppression but that it is a first step to reparations.”

Legacy admissions need to end.

The demographics of sports teams must mirror the student body’s, meaning that the Department of Athletics needs to begin rigorous, intentional recruiting from non-white sports programs. The department must also work to retain students of color in its programs.

The Office of Advancement needs to hire more Black staffers, and it must “appreciat[e] Black alumni and other alumni of color.” The office must uphold the invaluable contributions that Black alumni have made to the community, immediate and otherwise, a correction on its “misunderstanding that value is only found in money because people are not resources.”

Lastly, the document posits that when Martin has completed her term as president, her successor as president must be a Black person: “it has long been acceptable for Amherst to not yet have had a Black president, despite previous Black president-candidates.”

Comments ()