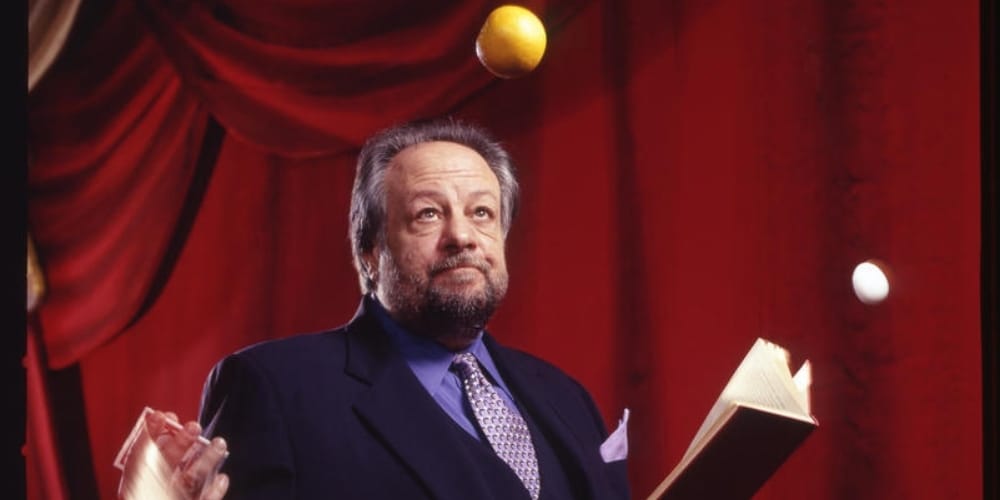

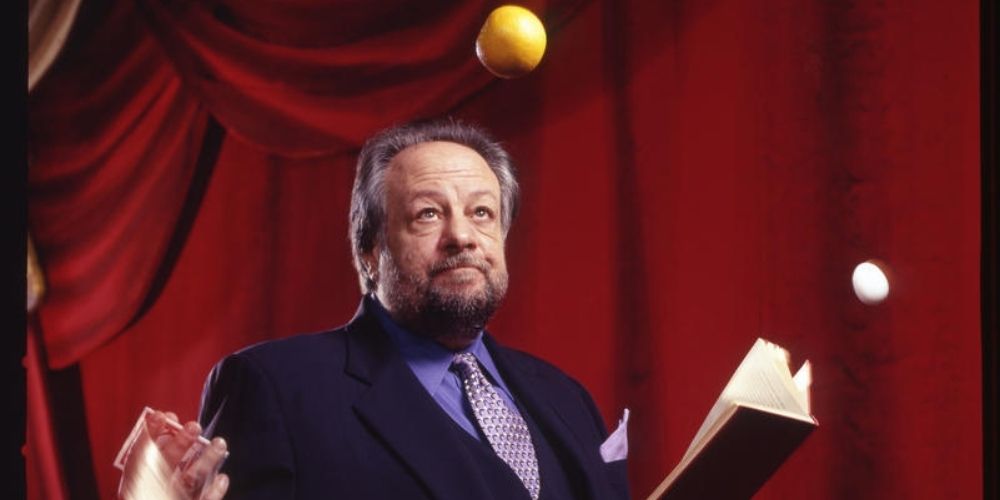

Ricky Jay: Master of the Deck, Maker of Magic

For Ricky Jay, magic is not just party tricks, it is a universalizing world view. He fluidly slips from storytelling to history to quippy old French verse. Magic collects these interests into a singular, convergent point.

In any field of art, it is valuable to know how to be good, so that when someone is amazing, you can understand the stakes of that success. Magic is no different, and magician Ricky Jay in “Ricky Jay and his Fifty Two Assistants” understands that truth perfectly.

Ricky Jay, who died in 2018, was a magician with a long career, an actor in many shows and movies and an absolute master of cards. That was apparent, almost immediately, even over the 360p resolution of the likely illegal Youtube upload of “Ricky Jay and his Fifty Two Assistants” I watched this past week.

In this 1996 show, he performs simply, elegantly, with gentle histrionics. He is sometimes comedic, sometimes teacherly, but always erudite and verbose. He fidgets and jokes and, even on one or two occasions, stumbles over his own words. The cards — the titular fifty two assistants — dance and amaze. It is a small show in both scope and audience. Jay’s ambition is cards, and in his hands, cards become enough.

The route by which I ended up watching this 25-year-old magic special — on Youtube in multiple delicate slices over a couple days, then again, and then a documentary about Jay, also on Youtube, also in poor quality, also probably illegal — is as mysterious as that algorithm which rules my recommendation bar. Ricky Jay is a name I have heard, often called “the magician’s magician.” But I’m not a magician, nor am I even really able to perform tricks. So I’ve never had a reason to watch him.

This past year, however, I’ve submerged myself in the breadth of magic videos circulating on YouTube, mostly from programs like “Penn & Teller: Fool Us,” in which Penn Jillette and Teller try to figure out how other magicians perform their tricks. Most of the time, they do figure it out. For me, it has been a distraction from the otherwise baseline misery of the past year.

But I didn’t find Ricky Jay through Youtube recommendations. Instead, I stumbled upon him by the outdated, un-algorithmic, bespoke word of mouth. It was a passing eulogy on Ricky Jay that turned me onto this special. The previous year of floating through magic videos felt, then, like a year of intense training, all building up to this: to Ricky Jay. Finally, I could watch the magician’s magician. Not quite through a magician’s eyes, but through something approximating and approaching what a magician might see.

To really appreciate “Fifty Two Assistants,” you need to know a little about how to do magic. Jay first explains the difficulty of the tricks he performs, then performs them flawlessly. A middle deal, where one deals from the middle of the deck but makes it appear like they are dealing from the top, is not impressive to the person that does not understand magic is taking place. He contextualizes the tricks, as well as hyping up their impossibility, acting as our gondolier through the mysterious, murky waters of magic.

Jay doesn’t explain everything though. He ends the show with a perfect execution of the classic cups and balls, a trick involving three cups and three balls which seem to slip between the cups. Even a show about cards cannot escape this ancient trick. To know nothing about cups and balls and to see Jay perform this trick leaves one feeling, perhaps, deflated — what a commonplace trick, to end such a spectacular show. But knowing a little about cups and balls, I left the show elated. I saw proudly, at first, how the balls were being snuck under the cups, where he had placed and taken them. But he tricks further and more flawlessly. The final product is not for the naive audience, but for the magically inclined. It is a wink and a nod to the fellow enthusiast, amatuer or magically curious.

It is a masterclass performance, an original rendition of the cups and balls, wrapped inside a history lesson about cups and balls, so effectively beautiful as a trick that I have seen his kind of cups and balls routine recreated countless times elsewhere. But it was, in its time, a new rendition of a cliché so original that others could not help but copy it.

Jay is so compelling because he approaches magic with a deadly seriousness, yet comes off jokingly. For Jay, magic is not party tricks, it is a universalizing world view. Jay is an eclectic personality, which is obvious even in the show. He fluidly slips from storytelling to history to quippy old French verse. His magic collects these interests into a singular, convergent point. It was the original refuge of the cheat, but cheat as intellectual rogue. Jay traces magic’s historical tracks backwards, finding, among cheats, friends and mentors. In this way, magic becomes a medium of storytelling. Magic is a profession of wisdom and secrets, of passed down knowledge, of oral stories. Jay was once, clearly, its head shaman.

Many contemporary magicians, the most obvious being Derek DelGaudio, were clearly influenced by Jay and have adapted his central motifs — a small crowd, intimately grasped by the sheer mastery of a single individual over a deck of cards — for their own performances and stories. But it isn’t the cards alone that make the performance a spectacle. To those cards, the performer adds storytelling, and in the startling puff that follows, it is perhaps in the mysterious combination of cards and story that we can say the magic happened.

Comments ()