The Art of The Archive: Feeling Histories — Alumni Profile, Siobhan McKissic ’12

Siobhan McKissic ‘12 is guided by endless curiosity for the past and the present, and brings others in touch with the intimate histories surrounding them.

When I called Siobhan McKissic ’12 and asked them if I could record our conversation, and they laughed boisterously. “Okay,” she chuckled, “I’ll try not to say anything wild.”

As our Sunday night call drew on for 90 minutes, I was very hands-off. I asked McKissic straightforward questions, and I got informative answers: their journey to library and archival work was preceded by a period of forced commitment to economics and suppression of their love for art. But, like objects in an archive, the steps in McKissic’s narrative are just islands in the endlessly exciting sea of their passions and life experiences: at one point, they moved from talk of House music to Sir Isaac Newton in the span of five minutes.

I’m grateful that McKissic allowed me to record our call, because so much of her personality was contained in the rambles and laughs that you can’t capture in handwritten notes.

From Chicago, to Amherst, and Back Again

Since I’m also from Illinois, I was naturally curious as to how McKissic made her way to the Pioneer Valley. Starting in middle school, before McKissic even had ideas about college, their mother had sent them to summer camps at Amherst. “When I started considering college, Amherst seemed like a perfect fit. I was already familiar with the area, my mom was comfortable sending me there, and I wanted a small school since I was coming from Whitney Young High School, which is huge,” they said.

Attending the college’s pre-admission diversity program sealed the deal. “I had visited Williams the week before … and I really didn’t like it,” McKissic joked, “Then I came to Amherst, and I absolutely loved everyone in the program.”

McKissic arrived as a prospective economics major. Their mom is an accountant, and McKissic always excelled at math. “But after a couple of semesters, I had only taken one economics class, and the rest was theater, music, and women and gender studies,” she said. “Eventually, I realized that no matter how much I tried to fight against it, I was going to end up making art. I just had to.”

They ended up doing an art and music double major, specializing in sculpture/printmaking and jazz, respectively. “My art advisor was [Senior Resident Artist in the Department of Art and the History of Art] Betsey Garand, and I will forever adore her. And my music advisor was [Professor of Music] Klara Moricz, she was also fantastic,” McKissic gushed. “Her and Ann Maggs, who’s the music librarian. They’re truly some of the most supportive people ever.”

After completing her studies, and devoting many hours to the various performance groups on campus, McKissic went home to Chicago. She confessed to me that she only visited the college’s Archives once during these four years. Little did they know that their brief stint in the Amherst Music Library foreshadowed a fascinating career to come.

“Doing Right by This Material”

“When I went home, I was really committed to making art and performing, so that meant I needed to find a real job,” McKissic quipped. Expecting a classic story of a young artist falling to the demands of capitalism, I was pleasantly surprised to find that their story had a happy ending, in large part due to their own joie de vivre.

“To anyone who’s graduating soon, especially artists, I’d advise you to take the weirdest but most exciting jobs you can find,” McKissic said. “When I was working in Chicago, I was a cheesemonger and then had a job painting four-foot tall bobbleheads for a grocery store display. Really weird stuff.”

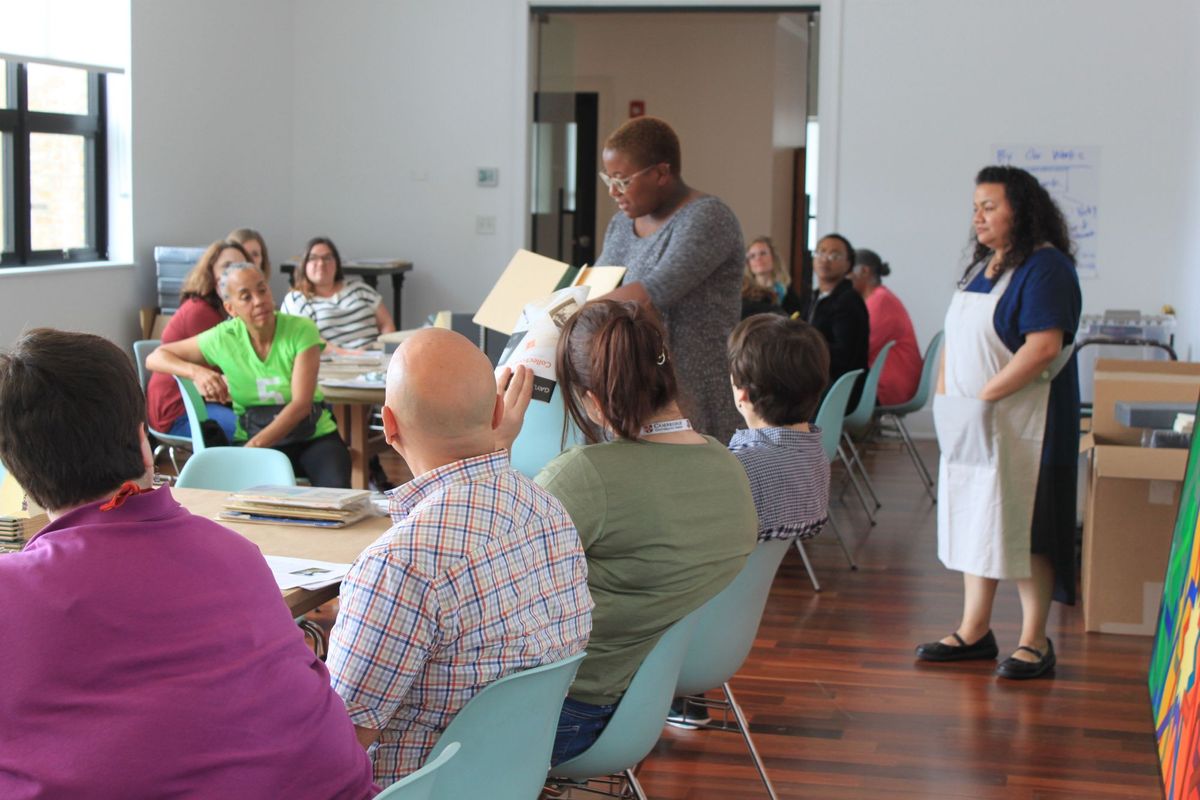

“But what I really was passionate about was art, and connecting with Black people on the South Side — people like me,” McKissic elaborated. In 2014, she grounded herself in this world and began interning for the renowned Theaster Gates, a University of Chicago professor of visual arts and a social practice installation artist. McKissic got “thrown into” processing Gates’ collection of memorabilia and letters that related to Black history in the United States. It was here that they discovered a passion they couldn’t shake.

“There was some really, really difficult materials — like wills where men were passing down enslaved people to their family members and some really racist figurines,” McKissic said, “But there was also sheet music from some of the first Black woman composers and Black literature from the late 1700s. And I felt empowered to learn as much as I could so that I could teach my community how to handle these materials.”

By “how to handle these materials”, McKissic meant something physical, due to the artifacts’ fragility, intellectually, and personally. They brought up some other collections they’d worked with: the Frankie Knuckles Collection and the Gwendolyn Brooks Papers. Knuckles was a pioneer of the House music genre, the precursor of EDM, and Brooks was the first Black person to win a Pulitzer Prize. “She [Brooks] was a mother figure to so many artists of Chicago’s Black Arts Movement in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. And, quite frankly, there’s another Black Arts Movement happening now.”

“I needed to make sure that I was doing right by this material.

Detective Work and the Politics of Things

To ensure that, McKissic left Chicago in 2016 to attend library school at the University of Illinois in Urbana Champaign (UIUC). It was here that they learned how to be “professionally nosy.”

“Imagine something happens to you, like, today and someone goes and tries to piece together how you felt and how you lived based on what you left behind,” McKissic said, “That’s basically what I do every day.”

In her academics and in her graduate assistantship at the UIUC Rare Book and Manuscript Library, McKissic dove into the nitty gritty of what it means to be an archivist, a keeper of history. “I find the ethical code of librarianship really fascinating,” she remarked, “because people should have free access to knowledge, and you want to preserve their research privacy. I love helping people find stuff, but I also want to make sure you’re coming away with the skills to do it on your own.”

One thing that complicates the archivist’s ideal of free knowledge is that politics, past and present, inform our decisions about what to keep and what to exile to the forgotten corners of history. “I’ve been told that I’m spoiled because I’ve almost exclusively worked with Black materials,” McKissic laughed, “and that is a really unusual experience.”

They went on. “We need to make sure we’re devoting our energies to saving other histories, because most of the history we have saved deals with white men. No shade to them, but if we want to truly have an understanding of history … they’re not even the majority of people.”

Later, McKissic officially became the archivist for the UIUC Rare Books Library. There, they worked with all types of histories, like a Sir Isaac Newton manuscript with notes on the fabled Philosopher’s Stone. But those materials that dealt with non-white-men were still some of the most moving. McKissic told me that the Rare Books Library has one of the original copies of the Emancipation Proclamation. “Not the one Lincoln wrote,” they clarified, “but pocket-sized copies of the Proclamation that Union Soldier’s disseminated throughout the South after Lincoln’s announcement. They’re these tiny pieces of, like, newspaper print, and we have one of only several known copies.”

When McKissic pulled out the Proclamation for a group of high school students, one girl started crying. “She was so moved by it because it’s literally a document that told our ancestors, ‘You can leave. These people cannot keep you hostage anymore.’ Whether or not that history ended up being true, it’s still such a powerful experience to hold that document and think about how many people read it and learned they were free.”

“There aren’t many jobs you can do where you can connect people to history in that way.”

Creating New Histories

As of September 2021, McKissic transitioned out of managing archives to creating her own. They’re currently working as a Visiting Faculty Design & Materials Research Librarian for UIUC’s Ricker Library of Art & Architecture and beginning construction on a “materials library.”

“Right now, it’s really only companies that have materials libraries — like the people who make your tupperware have an archive of all the different plastics that researchers can touch and learn about. But I’m trying to build something that’s public,” they said. McKissic is trying to build a library where people can learn about the building blocks of our environment and how our choices of materials impact us, not limited to the materials common to the United States.

Besides just the types of materials, McKissic is also considering the forms she wants them to take. Libraries can be very intimidating and cold-feeling, “so instead of a square sample of glass or satin, I could archive a Topo Chico bottle or a durag.”

McKissic is bringing together questions of sustainability, accessibility, and politics, all through a public university’s materials library; she’s working to create an archive of our material past and present, working to inspire change in a completely unexpected way.

When I asked them how they view Amherst as an institution, they hesitated for the first time during our entire conversation. “After working in higher education, I’ve come to see that my criticisms of Amherst are really criticisms of higher education in general: balancing the money interests with the interests of students and professors. And because Amherst is small, they’ve actually had more freedom to make choices that improve inclusivity.”

McKissic isn’t satisfied with the way things are, and views change as an “endless struggle.” Like Amherst, but in a more radical way, McKissic harnesses the power of smallness as they trek into the future — the infinite collectivities of bamboo mats, diaries, and newspaper scraps that humanize histories past and present.

Comments ()