The Indicator x The Student: “dead on arrival”

Originally published in the Fall 2022 edition of “The Indicator,” Managing Arts & Living Editor Madeline Lawson ’25 writes about an all-encompassing obsession.

There was a sale at Ace Hardware today: 40 percent off washers, so Ophelia walked home with tiny metal discs pinging around in his coat pocket. He didn’t have any particular use for them right now, but soon enough, he’d be stumped and a washer would sew it all together. How horrible it would be to be so close in the middle of the night and have to quit right before success, just because he’d passed up a sale.

When Ophelia got home he stuffed the bag of washers in one of his dresser drawers beside a good chunk of his savings, transformed into hardware and other essentials. He heated up a frozen lasagna. There was no dinner table, so he sat on his floor watching a show on his phone and glanced over at the machine in his bedroom corner. He thought: Tonight it will work. He had thought this every night for the last decade. He kept eating.

Old SNL clips weren’t distracting enough; Dana Carvey sketches held his attention for less than a minute. The other day he’d read an article about how people his age were so used to instant gratification that they couldn’t focus on anything. Of course he could focus. What was the portal, the pride of his life, if not driven by focus? But —

maybe he really wasn’t all that focused.

Maybe if he’d spent more time watching over the portal, instead of working and reading and texting friends, it would work. He abandoned his lasagna and leaned over to fiddle with it, though the sun was still watching.

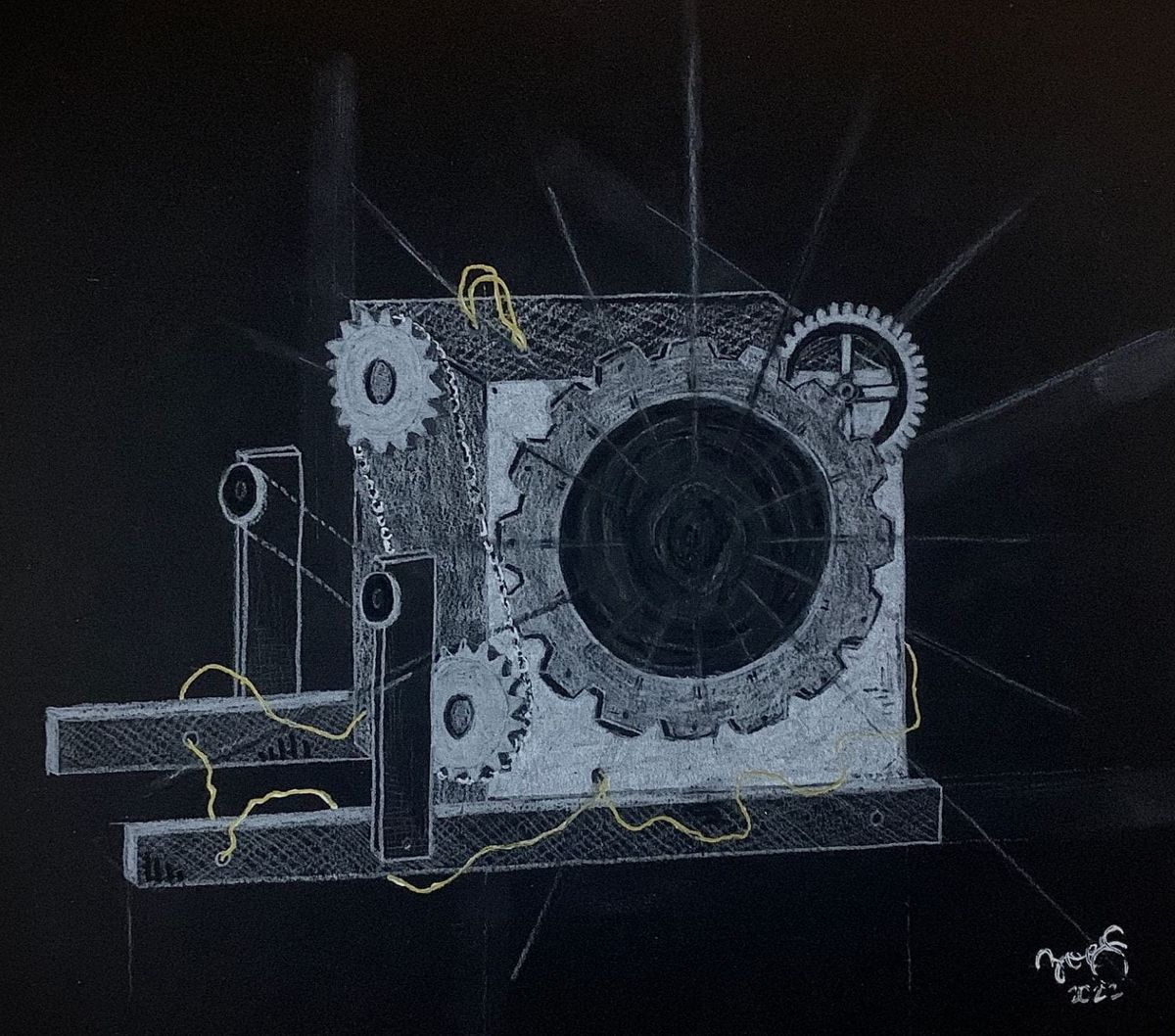

During the day Ophelia admonished himself for drawing circuit diagrams in the margins of meeting notes, and by night he kneeled before the metal shrine he’d been dragging around since high school. He hated it. It drove away the few visitors he had, too obviously ugly to be cited as an art project. If he got it right, though, its appearance wouldn’t matter. He wouldn’t cry about a dent in the frame, nor about a 10-year-old frayed wire. He would never think about it again.

He wrapped a copper wire around the base of the portal. His grandfather had been an electrician; Ophelia hadn’t ever even taken a trade class. He had done this for so long, though, that he figured he had to get it right one day. It was a fire hazard, one that would surely get him evicted if his landlord ever came in and saw it. The exposed wires were thrown over the metal base, barely hanging on. It wouldn’t catch fire. Would it be stupid enough to kill its creator? Or —

maybe the fire was the key. Maybe it would scrape the years off his bones, return his few gray hairs to the universe. It would clean him, absolve him, and turn him back, so this time, he could get everything right.

He would open a portal to another world, one where he didn’t have to cycle through roommates because they all kept getting married, where he didn’t carry around a name that made him sound less like a Shakespearean tragedy and more like a man who was couldn’t come up with something different when he transitioned. His creation was the only route to fixing his life.

He nourished it in hopes of it growing strong and making him proud. He was a horrible father. He stroked its metal casing and adjusted a wire, like tucking the hair behind a child’s ear. He was a fantastic father. What life would it have without him?

“How are you feeling?” he asked. “Anxious? Happy? Don’t you want to tell me what’s going on?”

It didn’t answer. He had an art history degree; maybe his friends, almost medical doctors now, could coax it from its catatonic state, but the creature in his room recalled the work of an artist Ophelia couldn’t remember. He could’ve written a paper about it.

“Hello? Are you going to speak today?”

The child stayed silent. Petulant, ungrateful child.

“What if I do this?” Ophelia adjusted the base and leaned up to catch the frame from falling.

No response. He thought about teaching it a lesson by hauling it down to the scrapyard and threatening to leave it there unless it acted right. Then: he would leave it, turn back to see his only child crashed in a trash incinerator, melted down for scrap parts, and become a new man. He would grieve. He would join a Dungeons and Dragons campaign, or maybe volunteer at a food shelter. He would notice when the sun set and when the day ended. Or —

maybe he was nothing without it.

Ophelia tucked it in, leaving it upright enough only for ease of use later, and laid himself down to sleep. Tomorrow — no, today, after a thousand work emails and a reheated lasagna — he would really breathe life into it.

Comments ()