The Indicator x The Student: “Do Zombies Dream of Electric Guitar?”

Originally published in the Fall 2023 edition of The Indicator, this piece by M. Lawson ’25 humorously invokes a seminar about zombification.

Up here, on the podium, is our subject’s soul-liver during the first stage of zombification. If you did the reading last night — and I know you did — you’ll remember the infection of the brain is a Hollywood lie. It begins in the soul, inside the liver, and because it’s a self-sustaining disease, it’s easy to blame someone for their affliction. However, it is similar to the lycanthrope in that their minds are completely powerless to the actions of their souls and bodies; unlike the werewolf, though, there is never any reversion back for the zombie.

So — our example for this chapter is a fifteen year old boy, a Canadian who loves The Office and skateboarding. He’s still pretty normal, but if you look at the ultrasound of the first-stage liver on your handout, you’ll see it has a sheen that the sample liver doesn’t. That’s the film, known as the encasement. The best example I can give you is to imagine that thin plastic sheet which covers a microwave meal wrapped around an organ, squeezing it only slightly, barely moving. Look at the healthy liver printed right beside it. It’s plump, while the other one is pressed and narrowed.

His soul is walking towards the end of his life, and why? Because he loves someone. Six someones, in fact, and he cycles through his loves every day. They all have some terribly irredeemable quality: one’s got a boyfriend, one’s got a girlfriend, one runs cross country, et cetera, et cetera. He does this, though, because his best friend recently got a girlfriend. Our subject has always done what his friend does, like skateboarding, but his envy is now treading into the worrisome. His friend, with his thousands of perceived accomplishments, has become an obsession, and stage one sets in.

Stage two is when the zombification begins to be dangerous to the subject. Patients lose sleep, eat less, and try to take on the demeanor of the object of belovedness, to varying degrees of success. For example, you might see someone who’s made themselves to become a complete twin of their obsession, but they look in the mirror and think it isn’t enough and that they must go further. They might cut their hair or get identical tattoos, for instance. I read a case, the other day actually, where a woman stole a car just because it was the same red as her obsession’s.

But, anyway, our subject doesn’t care anymore about The Office. After all, his best friend doesn’t like it. He prefers playing the guitar. Our subject reasons that he, too, should play the guitar. He spends all his money on one and wastes away watching Youtube videos to learn it. He dyes his hair red. He texts his friend at least ten times a day and imagines him with his girlfriend, while his partner-of-the-day rotates lazily in his mind. He reasons that they’ll be equal again, once he does all this, but he still feels like he’s losing to his friend. He is decomposing in a bin of his own envy, and no one notices. It’s hard to tell, at that age, what’s plain envy and what’s an eventual diagnosis. That’s why all of you who are interested in pediatric care should pay particular attention.

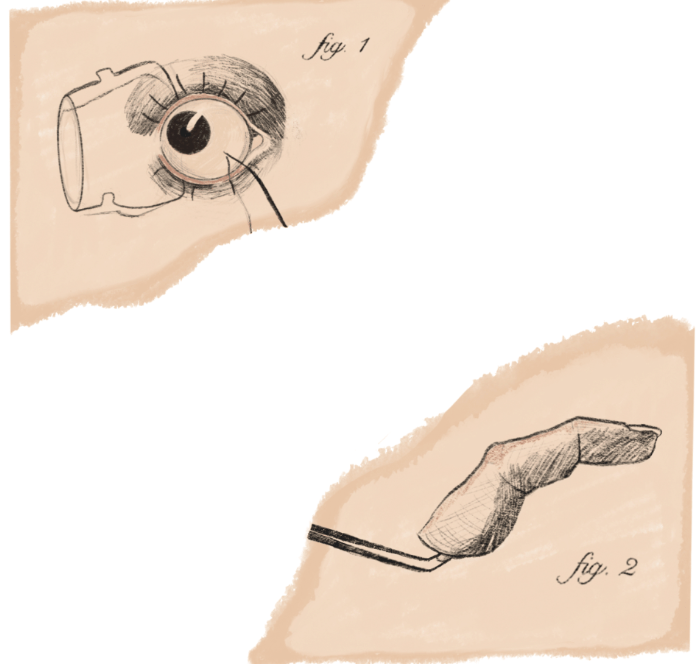

Come up here and touch his eye. This is from after he died, of course, once his body shut down, but the eye remains the same from after the third stage. It hardens while searching for the pulse of its desire and — no, you don’t need a glove, you won’t get sick — and it feels like a marble. When I touch my eye, it has a bit of give to it, but you can flick this one and it’ll sound hollow. It is so vacant that no blood even needs to flow through it; it is entirely controlled by the soul. That’s why there are no arteries visible.

Our test subject, now in the third stage, looks anemic, with no color behind his skin. He’s ashen, like a vampire — no, not a real vampire, one of the movie ones. Edward Cullen. We’ll get to that in a few weeks. At this point, the zombie decides he must take action, that he can’t live without a resolution, so he tries to take the victim of his obsession. His best friend, for example, woke up with two less fingers on his right hand, with our test subject trying to gnaw a third one off and licking the blood off of his hands. He was even regaining some blush on his cheeks, that’s how much of his friend he was eating. Remember — and you’ve got to write this down! — the friend cannot become zombified just because he was partially eaten. That’s often the first question victims ask.

Oh — good question! No, the fingers cannot be digested, because the body’s stopped functioning as human, which leads us into the final stage, so thank you. Once the soul stops feeding off of the obsession, either figuratively or literally, the body shuts down until death. The soul-liver is completely shriveled up. Look at the ultrasound on the back of your paper. Doesn’t it look like a little raisin? Without exposure to the object of desire, it becomes dehydrated and eventually the body dies.

Our test subject spent his final days strapped down in a hospital room in Halifax while his limbs writhed around, and he was gagged so as to stop him from gnawing at the redhead nurse. Without exposure to the victim, the soul-liver ceases in providing the body with a will to live. The body shuts down, part-by-part. In the subject’s case, his legs went still first, followed by the head and torso, so that he stopped breathing. His arms, living for days on those last pulses of the soul-liver, crossed over him and kept twitching. Reportedly, his fingers kept strumming and his left hand kept fretting the neck of an unreal guitar before they stilled.

Comments ()