Thriving Anime Club Reflects Nationwide Trend

Amherst's Anime Club hosts regular screenings, discussions, and cultural and social events surrounding the Japanese genre. Its popularity reflects broader trends in American culture.

If you venture over to Paino Lecture Hall in Beneski Museum of Natural History on Friday nights at 7 p.m., you’ll find a meeting of the Amherst College Anime Club. Whether or not you enjoy watching anime as a hobby, you’re almost certainly familiar with it. In fact, you probably consume Japanese media and culture without even knowing it. This is because in today’s American pop culture, Japanese culture is omnipresent. What was considered a niche subculture has emerged on the internet — anime scenes are often used as memes — as a key element of youth dialogue.

As anime has often been stigmatized in Western culture in the 21st century, it is no surprise that it has flourished on anonymous platforms such as Reddit, Twitter, and Youtube. Alden Parker ’26, a member of Anime Club, reflected that “had I not discovered anime by being a complete T.V. Tropes [a popular T.V. wiki forum] junkie, I probably wouldn’t be here.”

Amherst’s anime club is part of a larger effort to remove the anonymity from anime fans on college campuses, bringing the online community into real life.

It is unclear how long Anime Club has existed at the college. In the Frost Library stacks, you can find copies of anime that were gifted to the school by Anime Club as early as 2007, though no one in the club can say for sure when it started. The club currently has 87 members, and meets once a week on Friday nights.

Anime Club provides a centralized anime-viewing experience. There are no strings attached. There is no commitment. There is no entrance fee. No pressure. Anime Club screenings are a fun and inclusive viewing experience for people with any level of experience with the genre. Beyond simply watching anime, the club provides a setting for robust discussion and debate regarding the themes and messages of relevant shows.

If you’ve ever watched anime before, you know how complex the narratives and character arcs are, which prompts lively discussion. The club’s vice president, Jeff Zhang ’25, said that “people stay behind for 20 minutes or so discussing themes from that night’s showing, or really anything at all. The important part is that it all comes about organically.” On top of discussions, the club engages in karaoke, cooking-nights, and various social events throughout the year, including a trip to New York City ComiCon.

Anime Club’s efforts to make their interest mainstream come alongside a broader cultural shift. According to a report by Precedence Research, the global anime market was valued at $22.6 billion in 2020. By 2030, that number is expected to more than double, growing to about $48.3 million. Much of the growth is taking place in the U.S. and North America in general. Precedence Research theorizes that this is due to an increased presence of anime in American media.

Only a few years ago, I recall that watching anime was heavily stigmatized in American high schools. At least where I come from, popular dialogue among American teens dubbed anime uncool, or for kids, or exclusively for Asian people.

Considering this shift from anime being “uncool” to an acceptable staple of many people’s identity, I was curious to hear the thoughts of those who have experienced it firsthand.

“Before, simply having an interest in this stuff could more easily have gotten you side looks from behind the scenes, or comments such as ‘oh, you’re one of those people,’” Parker said. “This is why I got most of my initial exposure through reading, as even bringing anime up with friends could have been too much of a risk … Whereas now, I can be very open about my interests in anime especially because of the anime club. So the increase in popularity has been overwhelmingly positive in my opinion.”

Zhang, who grew up in Hong Kong, described his experience differently. “I started watching [anime] in sixth grade. In contrast to [Parker]’s experience, I started watching anime because it was cool. And, in China and Hong Kong, there’s not much of a stigma,” he said. “That is an English speaking phenomenon in the modern day.”

Anime Club encompasses people of many different racial, ethnic, and national backgrounds, and this diversity can be seen in the larger anime community as well.

Club member Cole Ammons ’23 touched on the influence that other cultures have had on anime’s growing popularity in America. “I would say there’s a pretty heavy influence of Black culture,” he explained, “Especially with shows like Dragon Ball. You’ve got [musical] artists [like] Thundercat who base their identity around anime, leading to songs like Dragon Ball Durag.”

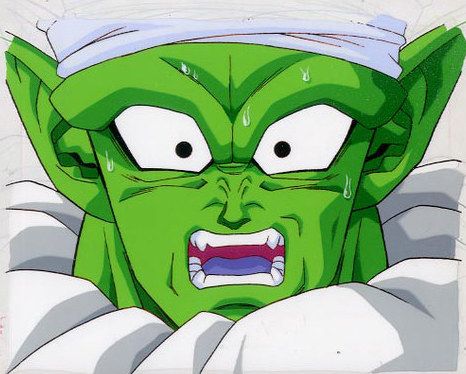

Ammons also commented on the fact that many fictional anime characters have been championed by the Black community, noting “for example, Piccolo [from Dragon Ball] was claimed by the Black community. Even though he is a green alien, everyone knows that he’s Black.”

To Ammons’s point, Jordan Calhoun wrote a brilliant piece for The Atlantic titled “Piccolo Is Black” detailing how this came to be. He described how animation had first depicted horribly racist caricatures of people of color, before moving to omit them altogether.

“The result was a generation of kids who learned to “code” characters, assigning them a race, sexuality, or other identities that weren’t specifically prescribed, but that were no less real to those of us who wanted to see ourselves reflected in a media landscape that wasn’t interested in us.”

Ammons also noted how recent generations of Black youth who grew up watching anime are now adults, and heavily impact the social narrative around these shows that permeates the internet.

“I think a lot of it has to do with the fact that kids who grew up watching Toonami are grown up. That’s that generation that were kids from 1997 to 2008,” he said. “Now those same people are active on Twitter, Youtube, Facebook, Instagram, etc. … Many of them make popular content and have far more influence than you’d imagine.” Indeed, many popular Black content creators on the internet include anime in their comedy.

To Ammons’s original point, anime’s rise in mainstream popularity has a lot to do with its popularity in the Black community and Black internet subcultures. This, too, is emblematic of the way America’s broader culture often grows out of the trends in Black communities.

As far as how cultural mixing impacts anime culture, for example, there’s so much more at play than what I’ve provided here.

What’s crucial to recognize, though, is the role Anime Club plays in this phenomenon of cultural production: It provides an inclusive environment where like-minded people can come together for screenings, discussions, cooking, singing, and much more. As anime cements itself in mainstream pop culture, student organizations such as Anime Club can give us a window into broader cultural phenomenons.

Comments ()