What Happens After Dorm Damage?

On the other side of every weekend, there’s someone cleaning up the mess —and the damage — left behind by parties. The Student spoke to custodial staff, supervisors, and directors to understand how repeated dorm damage has impacted them.

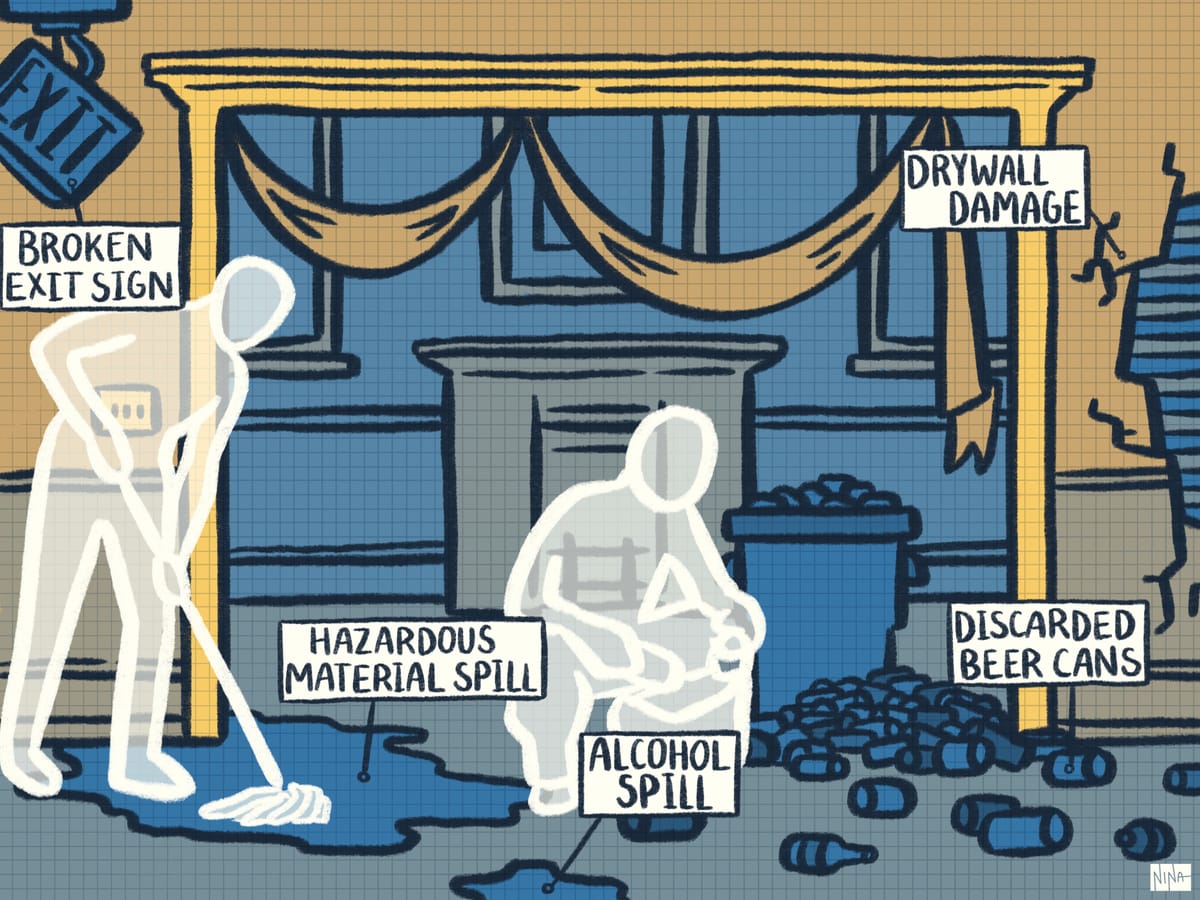

At the end of a weekend at Amherst, it’s common for dorm residents to see exit signs removed from their ceilings, vending machines tipped over and smashed, bathroom stall doors ripped off their hinges, and more — different types of dorm damage from weekend parties.

We know that when these incidents happen, someone has to fix it. What does that actually look like?

Three members of custodial staff, as well as supervisors and directors in the custodial and facilities departments, spoke about labor, time, cost, and how their lives have been impacted by incidents of dorm damage.

The process of work they described — discovering, accounting for, and repairing dorm damage — continues throughout the entire academic year, re-cycling after every weekend. Their voices provide insight into what kind of impact students really are making in the spaces we occupy. And while we might imagine the biggest burden of dorm damage as tied to the most egregious examples, custodians testified that even sticky, dirty floors and discarded cans left behind from a registered party can create more than five extra hours of labor for them.

The impact of these kinds of damages often slip below the surface of community perception. As Custodial Supervisor Liz Pereira said, “a lot of students, even faculty and other staff, don’t really know what goes on. We do a really good job covering it up.”

What happens after a dorm gets damaged, then, tells a larger story about the custodial system designed to keep our college clean and safe, and the power imbalances that underscore it.

Discovering the Damage

According to Pereira, the custodians who work on Saturdays, Sundays and Mondays are often the first people to encounter dorm damage after it occurs at parties over the weekend.

The custodial staff at the college consists of 55 people who work Monday through Friday, and 5 people who work Saturday and Sunday. A few additional custodians who sign up to work overtime often accompany the weekend team. The Monday through Friday team is responsible for cleaning academic, administrative, and residential buildings, and for completing regular disinfecting and cleaning. The weekend team is not responsible for regular disinfecting and deep cleaning, but come in to respond to the needs that emerge over the weekend, including replenishing items like toilet paper in the dorms, and emptying trash and recycling. They also respond to what the department calls “triage areas,” where hazardous dorm damage most often occurs.

When custodians encounter damage that can be hazardous — such as broken glass or biological waste — they must immediately clean it up. This is true every day of the week, but “because [students] party Friday night, Saturday night, you’re more likely to run into that stuff on the weekend,” said custodian Bryce Benware. Cleaning and responding to the “triage areas” therefore becomes a regular part of the weekend job.

Benware recounted one time when he signed up to work overtime hours on the weekend in Morris Pratt Dormitory, a “classic example” of a dorm where party damage often occurs. He recounted going up to the third floor bathroom to restock toilet paper and found that “the stall doors were ripped off the hinges and hanging … and inside the toilet, they took a bunch of paper towels, stuffed them into the toilet, threw three rolls of toilet paper on top of it, and then urinated all over it.” Although cleaning those toilets was not technically part of Benware’s job that weekend, the mess included biological waste and could pose a hazard to students, so, “I had to clean it.”

Because dorm damage is so concentrated over the weekends, taking weekend shifts becomes burdensome and undesirable. “It seems like in the beginning of the school year, you put the notice [for overtime] up, people sign up right away. And now it’s like, you get to the end of the week, and they’re still looking for people to come in,” said Benware. “I think a lot of people are a little discouraged to come in because they expect to have to deal with these very big messes and damage. It hurts morale a little bit.”

In addition, custodians who work Monday through Friday in dorms that tend to be party hotspots — Hitchcock, Seeyle, Mayo-Smith, Jenkins, and Morris Pratt — continue to bear the brunt of cleaning up party messes throughout the week. Even after the weekend team clears hazardous messes, remaining damage usually persists on Mondays and well into the week.

Ryan Furches, a custodian at the college, said that when he comes into work on a Monday, he always checks for outstanding and potentially dangerous damage first. Furches works cleaning Hitchcock Dormitory, one of the three dorms in the area known as the triangle, which he winkingly called the “Bermuda triangle” — a place where problems happen and things go missing.

“That’s the first thing I do, is check places out for [the] safety … of students as well as the staff,” he said.

Fixing the Damage

Once the damage has been identified, the process of fixing it comes next. Pereira said that once a custodian or supervisor assesses and documents the damage with photos, they reach out to the college’s service center, which serves as the “go-to point” in assigning different departments to create new work orders for fixing the different types of damage.

This often means enlisting the work of multiple departments on campus. “Dorm damage impacts … the entire community,” said Mitchell Koldy, Director of Auxiliary Services and Facilities, “but facilities, custodial and grounds, the electrical shops, and the building shops, get the full brunt of the damage.”

The electrical shop, for example, is responsible for replacing broken exit signs. The maintenance shop covers broken doors, as well as paper towel holders or soap dispensers pulled off the walls. The service center will call in plumbers for toilets clogged with paper towels.

The college’s party policy gives students hosting registered parties a chance to clean up their non-hazardous messes the next day. Reserving a space for a party technically entails the responsibility of cleaning, but Furches said that usually doesn’t happen. “If they don’t do it, then I have to take over responsibility to clean and use overtime to clean up those messes,” he said.

Furches explained some of the process of cleaning a dorm after a messy party. “The first clean, it’s called a dry clean. Students leave a lot of cans and bottles … so the first thing we need to do is clean up all that and make sure it’s taken care of,” he said.

He described the process of getting rid of cans and bottles as being “like an Easter Egg hunt … they’re under the couches, they’re over by the window, they’re in drawers, they’re in the bathroom, they’re in the stairwell. I have to collect all that trash. I don’t feel like playing that game on a Monday.”

After the dry clean, Furches said, “the second thing is a wet mop.” Custodians sometimes use an iMop, a human-driven machine that mops the floor with a wet brush while vacuuming at the same time. Pereira estimated that custodians typically have to mop the entire space two to three times to fully disinfect the floors and eliminate the smell of alcohol, which they use special chemicals for.

Furches estimated that it takes him an hour to two hours to finish mopping with the iMop machine, and more on days when he has to use a regular bucket and mop. The stickier the floor, the more rounds of mopping are required, and because you need to let the floor dry between the mops, he explained that sometimes it can take up to two days to completely finish cleaning a floor.

When the floor is sticky with spilled alcohol, the walls often are too. Their cleaning requires custodians to use sponges, chemicals, and magic erasers, a process Pereiraestimates can take up to two hours by itself.

Custodians are also trained in cleaning hazardous messes from parties, such as vomit and blood. Furches said that these kinds of cleanups, though small, usually take about an hour or two because of the deep disinfecting required. But “it depends on what it is, and the amount of it. Sometimes, if the vomit is dry, we’ve got to scrape it and put it in the trash, and then we have to do a hand mop, or use a chemical sponge. Then once that’s been cleaned, we have to mop it again,” he said. For safety reasons, everything that custodians use to clean up biological waste has to be discarded after use, even tools such as dustpans.

Messes like these happen after parties every weekend, for the entire year, custodians said. While cans and a sticky floor are certainly not the most shocking instances of dorm damage that occur, these regular messes make their own heavy impact when added up. “You have a custodian who has two, three times the mess of a normal [day], and it’s a bad mess. It makes the custodians’ work a little heavier,” said Benware. “Which to me is okay, if you all make extra trash or whatever … but when you’re picking up 100 beer cans — and that’s not an exaggeration — they’ll be all over the common rooms, beer all over the wooden floors. It comes off to me as kind of disrespectful.”

This cleaning responsibility comes on top of other expected job duties. According to a fun fact posted on the custodial department’s page on the college web page, a custodian at Amherst is “responsible for the upkeep of 43,000 square feet each day” — the equivalent of cleaning 35 average sized homes. The added work of cleaning up messes and damages always requires someone to work overtime hours. “To cover for the time that [custodians] spend doing this out of their normal schedule, we give them overtime,” said Pereira. “Either they stay at the end of the day, which is [at] 2:30 pm, or they come in early the next day, at 4:00 in the morning.”

Impacts on Custodians

While harder to quantify, dorm damage also impacts the lives, thoughts, and emotions of the people who end up fixing it.

“That’s the way they treat us … like trash. Because we are the ones who clean,” said Employee A, another custodial employee who preferred to remain anonymous due to fear of retaliation from students or the administration.

“Every morning is filled with stress and frustration because you don’t know what might happen during your shift,” they said.

“We are all adults,” said Employee A, but they don’t feel that the behavior reflected in dorm damage acknowledges that.

Pereira reflected on the impact of damage on staff as a whole. “Especially after the Plimpton incident, we had a couple of custodians come forward and say, ‘this is a morale killer.’ You’re always cringing on a Monday to come to work and [see] what you’re going to find in the dorm,” she said.

Koldy brought up one incident he found particularly disturbing, when students in Seelye defecated in feminine hygiene boxes and smeared feces on the walls of the bathroom. He recounted the impactful way that staff told him about how the incident affected them: “Mick, can you imagine a custodian coming home and having to explain to their family going around the dinner table [saying] ‘hey, what did you do today?’ ‘I’m going to tell somebody that I had to clean feces off of a wall or out of a feminine hygiene box.’ How disrespectful is that?”

Imagine someone asks you, “‘How was your day?’” he said. “What do you say?”

Furches says when he comes into work on a Monday, “I just do it, I finish it, and then afterwards it actually feels good to have it all done and cleaned up. But at the start, I’m like, ‘ugh, come on,’” he said. “I don’t look forward to going to work every Monday … because of the weekend.”

Benware emphasized the difference between messes that are made irresponsibly and messes that are made deliberately. “I was 18, 19, 20, too. And I lived like an 18, 19, or 20 year old. And so I try not to take things personally,” he said. “But when you come into those deliberate messes, that’s when it kind of gets a little discouraging.”

Employee A spoke about a power imbalance between students and custodians on campus. Students will always have the ability to keep making the kinds of messes and damages that are not strictly prohibited by the college, but make work significantly more difficult for custodians, they said. For this reason, if a custodian were to “tattle” on students for behavior that makes cleaning harder, students could get angry and retaliate. Because of this, Employee A said they do not feel comfortable reporting damage, let alone the actions of specific students or student groups.

For this reason, Employee A said that oftentimes, the damage custodians have to clean goes unreported and unrecognized. “There are [custodians] who just do it, who clean it up and don’t say anything because it’s not worth filing a complaint in the office … they don’t do anything,” said Employee A. A lack of meaningful response to official reports leaves custodians without much choice when they encounter damage or a mess they feel they should not have to clean. “Do you clean it, or leave it like that?” Employee A ironically questioned.

Custodians also shared their broader reflections about why the damage might be occurring, and what it means for the college in the bigger picture.

Benware said that his perspective has been shaped by spending so much time caring for buildings at the college, and feels that “the college tries to provide nice spaces for you all … I really don’t know what to say about it, because a lot of people pay to be here, to be in these buildings. They live in them. It kind of makes you wonder why they treat them the way they do.”

He feels that dorm damage has gotten to a point where it is “so frequent that I would consider it a behavior … and you have to kind of wonder, why is that? If you can’t figure out why, you can try to ask, is there anything you can do to maybe address the issue and deter students from damaging the property?”

Employee A said the pay custodians receive is not enough compensation for the work they have to do. When dorm damage occurs, “it’s more work, but they don’t consider that in the pay,” they said. Employee A brought up the fact that they could work in a restaurant for the same wage they receive to work in custodial and clean messes that require large amounts of labor.

Benware said he and other custodians don’t know whether the college is making efforts to change this behavior. “It seems like that type of behavior isn’t really addressed by the college, and staff notices that,” he said. “For all I know, the college could be trying to do some things to address the issue, but … they’re not very transparent about how the behavior is actually treated, and I think that’s an issue too.”

Thoughts on Community

Custodians said that dorm damage connects to a broader feeling that students don’t recognize their importance in the community and the scope and impact of their jobs.

“Janitors are part of the front line … of this college,” said Furches. “I wish [students] understood how much we keep the college clean — and [that] we keep it safe, as well … That our job is a very important job.”

Benware emphasized that students only see a fraction of what goes into the job. “You might see a custodian mopping the floor, or vacuuming, or whatever. So you know they mop or vacuum, but you might not realize how much of everything they do,” he said.

He recounted working in a dorm on the first year quad where, “it kind of felt like walking through New York City … you just go about your business, and the students go about theirs. You don’t know much about them, and they don’t really pay much mind to what you’re doing. You’re just two separate beings doing your thing in the same space.”

Benware hopes to build more community among staff departments and students. “We work for the same people … the same person signs our checks. You all are part of that same institution. So I think it should feel like [that],” he said.

Comments ()